Purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French)[1] is a passing intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul. A common analogy is dross being removed from metal in a furnace.

In Catholic doctrine, purgatory refers to the final cleansing of those who died in the State of Grace, and leaves in them only "the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven";[2] it is entirely different from the punishment of the damned and is not related to the forgiveness of sins for salvation. A forgiven person can be freed from their "unhealthy attachment to creatures" by fervent charity in this world, and otherwise by the non-vindictive "temporal (i.e. non-eternal) punishment" of purgatory.[2]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

In late medieval times, metaphors of time, place and fire were frequently adopted. Catherine of Genoa (fl. 1500) re-framed the idea as ultimately joyful. It has been portrayed in art as an unpleasant (voluntary but not optional) "punishment" for unregretted minor sins and imperfect contrition (fiery purgatory) or as a joyful or marvelous final relinquishment of worldly attachments (non-fiery purgatory.)

The Eastern Orthodox churches have somewhat different formulations of an intermediate state. Most Protestant denominations do not endorse the Catholic formulation. Several other religions have concepts resembling Purgatory: Gehenna in Judaism, likewise al-A'raf which is a area to cleanse "neutrals" in Islam, Naraka in Hinduism.

The word "purgatory" has come to refer to a wide range of historical and modern conceptions of postmortem suffering short of everlasting damnation.[3] English-speakers also use the word analogously to mean any place or condition of suffering or torment, especially one that is temporary.[4]

History of the belief[edit]

While use of the word "purgatory" (in Latin purgatorium, a place of cleansing, from the verb purgo, "to clean, cleanse"[5]) as a noun appeared perhaps only between 1160 and 1180,[6]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". giving rise to the idea of Purgatory as a place,[7] the Roman Catholic tradition of purgatory as a transitional state or condition has a history that dates back, even before Jesus Christ, to the worldwide practice of caring for the dead and praying for them and to the belief, found also in Judaism, which is considered the precursor of Christianity, that prayer for the dead contributed to their afterlife purification. The same practice appears in other traditions, such as the medieval Chinese Buddhist practice of making offerings on behalf of the dead, who are said to suffer numerous trials.[3]

The Catholic church found specific Old Testament support in after-life purification in 2 Maccabees 12:42–45,[8] part of the Catholic biblical canon but regarded as apocryphal by Protestants and major branches of Judaism.[9][10][3] According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, praying for the dead was adopted by Christians from the beginning,[11] a practice that presupposes that the dead are thereby assisted between death and their entry into their final abode.[3] The New American Bible Revised Edition, authorized by the United States Catholic bishops, says in a note to the 2 Maccabees passage:

"This is the earliest statement of the doctrine that prayers and sacrifices for the dead are efficacious. …The author…uses the story to demonstrate belief in the resurrection of the just, and in the possibility of expiation for the sins of otherwise good people who have died. This belief is similar to, but not quite the same as, the Catholic doctrine of purgatory."[12]

Tradition, by reference to certain texts of scripture, speaks of the process as involving a cleansing fire. According to Jacques Le Goff, in Western Europe toward the end of the twelfth century Purgatory started to be represented as a physical place,[6]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". Le Goff states that the concept involves the idea of a purgatorial fire, which he suggests "is expiatory and purifying not punitive like hell fire".[13]

At the Second Council of Lyon in 1274, when the Catholic Church defined, for the first time, its teaching on purgatory, the Eastern Orthodox Church did not adopt the doctrine. The council made no mention of purgatory as a third place or as containing fire,[14] which are absent also in the declarations by the Councils of Florence (1431–1449) and of Trent (1545–1563).[15] Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI have written that the term does not indicate a place, but a condition of existence.[16][17]

The Church of England, mother church of the Anglican Communion, officially denounces what it calls "the Romish Doctrine concerning Purgatory",[18] but the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Churches, and elements of the Anglican, Lutheran, and Methodist traditions hold that for some there is cleansing after death and prayer for the dead.[19][20][21][22][23] The Reformed Churches teach that the departed are delivered from their sins through the process of glorification.[24]

Rabbinical Judaism also believes in the possibility of after-death purification and may even use the word "purgatory" to describe the similar rabbinical concept of Gehenna, though Gehenna is also sometimes describedLua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Category handler/data' not found.[<span title="Script error: No such module "delink".">by whom?] as more similar to hell or Hades.[25]

Christianity[edit]

Some Christians, typically Roman Catholics, recognize the doctrine of purgatory. The Eastern Orthodox are less likely to use the term, although they acknowledge an intermediate state after death and before final judgment, and consequentially offer prayers for the dead.

Protestants usually do not recognize purgatory as such: following their doctrine of sola scriptura, they claim Jesus is not recorded mentioning or otherwise endorsing it, and the old-covenant work 2 Maccabees is not accepted by them as scripture.

Catholicism[edit]

The Catholic Church holds that "all who die in God's grace and friendship but still imperfectly purified" undergo a process of purification after death, which the church calls purgatory, "so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven".[26]

Though in popular imagination Purgatory is pictured as a place rather than a process of purification, the idea of Purgatory as a physical place is not part of the church's doctrine.[16] However, the church's understanding has typically been that purgatory has a temporal (temporary, terminating, non-eternal) component with only God being outside of time.[27] Fire, another important element of the Purgatory of popular imagination, is also absent in the Catholic Church's doctrine.

Purgatory and indulgences are defined (i.e. official Catholic) doctrines, unlike limbo. Catholicism bases its teaching also on the practice of praying for the dead, in use within the church ever since the church began, and mentioned in the deuterocanonical book 2 Maccabees 12:46.[28]

The purgatory of Catholic doctrine[edit]

At the Second Council of Lyon in 1274, the Catholic Church defined, for the first time, its teaching on purgatory, in summary two points:

- some saved souls need to be purified after death;

- such souls benefit from the prayers and pious duties that the living do for them.

The council declared:

[I]f they die truly repentant in charity before they have made satisfaction by worthy fruits of penance for (sins) committed and omitted, their souls are cleansed after death by purgatorical or purifying punishments, … And to relieve punishments of this kind, the offerings of the living faithful are of advantage to these, namely, the sacrifices of Masses, prayers, alms, and other duties of piety, which have customarily been performed by the faithful for the other faithful according to the regulations of the Church.[29]

A century and a half later, the Council of Florence repeated the same two points in practically the same words,[30] again excluding certain elements of the purgatory of popular imagination, in particular fire and place, against which representatives of the Eastern Orthodox Church spoke at the council.[31]

The Council of Trent repeated the same two points and moreover in its 4 December 1563 Decree Concerning Purgatory recommended avoidance of speculations and non-essential questions:

Let the more difficult and subtle "questions", however, and those which do not make for "edification" (cf. 1Tm 1,4), and from which there is very often no increase in piety, be excluded from popular discourses to uneducated people. Likewise, let them not permit uncertain matters, or those that have the appearance of falsehood, to be brought out and discussed publicly. Those matters on the contrary, which tend to a certain curiosity or superstition, or that savor of filthy lucre, let them prohibit as scandals and stumbling blocks to the faithful.[32]

Catholic doctrine on purgatory is presented as composed of the same two points in the Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, first published in 2005, which is a summary in dialogue form of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. It deals with purgatory in the following exchange:[33]

210. What is purgatory?

- Purgatory is the state of those who die in God's friendship, assured of their eternal salvation, but who still have need of purification to enter into the happiness of heaven.

211. How can we help the souls being purified in purgatory?

- Because of the communion of saints, the faithful who are still pilgrims on earth are able to help the souls in purgatory by offering prayers in suffrage for them, especially the Eucharistic sacrifice. They also help them by almsgiving, indulgences, and works of penance.

These two questions and answers summarize information in sections 1030–1032[34] and 1054[35] of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, published in 1992, which also speaks of purgatory in sections 1472−1473.[36]

Role in relation to the church[edit]

The prayers of the saints in Heaven and the good deeds, works of mercy, prayers, and indulgences of the living have a twofold effect: they help the souls in purgatory atone for their sins and they make the souls' own prayers for the living effective,[37] since the merits of the saints in Heaven, on Earth, and in Purgatory are part of the treasury of merit. Whenever the Eucharist is celebrated, souls in Purgatory are purified - i.e., they receive a full remission of sin and punishment - and go to Heaven.[38]

Role in relation to sin[edit]

According to the doctrine of the Catholic Church, those who die in God's grace and friendship imperfectly purified, although they are assured of their eternal salvation, undergo a purification after death, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of God.[39]

Unless "redeemed by repentance and God's forgiveness", mortal sin, whose object is grave matter and is also committed with full knowledge and deliberate consent, "causes exclusion from Christ's kingdom and the eternal death of hell, for our freedom has the power to make choices for ever, with no turning back."[40] Such sin "makes us incapable of eternal life, the privation of which is called the 'eternal punishment' of sin".[41]

Venial sin, while not depriving the sinner of friendship with God or the eternal happiness of heaven,[42] "weakens charity, manifests a disordered affection for created goods, and impedes the soul's progress in the exercise of the virtues and the practice of the moral good; it merits temporal punishment",[42] for "every sin, even venial, entails an unhealthy attachment to creatures, which must be purified either here on earth, or after death in the state called purgatory. This purification frees one from what is called the 'temporal punishment' of sin".[41]

"These two punishments must not be conceived of as a kind of vengeance inflicted by God from without, but as following from the very nature of sin. A conversion which proceeds from a fervent charity can attain the complete purification of the sinner in such a way that no punishment would remain."[41]

Joseph Ratzinger has paraphrased this as: "Purgatory is not, as Tertullian thought, some kind of supra-worldly concentration camp where man is forced to undergo punishment in a more or less arbitrary fashion. Rather it is the inwardly necessary process of transformation in which a person becomes capable of Christ, capable of God, and thus capable of unity with the whole communion of saints".[43]

This purification from our sinful tendencies has been compared to rehabilitation of someone who needs to be cleansed of any addiction, a gradual and probably painful process. It can be advanced during life by voluntary self-mortification and penance and by deeds of generosity that show love of God rather than of creatures. If not completed before death, it can still be needed for entering the divine presence.[44]

A person seeking purification from sinful tendencies is not alone. Because of the communion of saints: "the holiness of one profits others, well beyond the harm that the sin of one could cause others. Thus recourse to the communion of saints lets the contrite sinner be more promptly and efficaciously purified of the punishments for sin".[45] The Catholic Church states that, through the granting of indulgences for manifestations of devotion, penance and charity by the living, it opens for individuals "the treasury of the merits of Christ and the saints to obtain from the Father of mercies the remission of the temporal punishments due for their sins".[46]

St Catherine of Genoa[edit]

On the cusp of the Reformation, St Catherine of Genoa (1447–1510) re-framed the theology of purgatory as voluntary, loving and even joyful:

"As for paradise, God has placed no doors there. Whoever wishes to enter, does so. An all-merciful God stands there with His arms open, waiting to receive us into His glory. I also see, however, that the divine presence is so pure and light-filled – much more than we can imagine – that the soul that has but the slightest imperfection would rather throw itself into a thousand hells than appear thus before the divine presence."[47]

So purgatory is a state of both joy and voluntary pain:

Again the soul perceives the grievousness of being held back from seeing the divine light; the soul’s instinct too, being drawn by that uniting look, craves to be unhindered”

— Treatise on Purgatory, Chapter 9

Pope Benedict XVI recommended to theologians the presentation of purgatory by Catherine of Genoa, for whom purgatory is not an external but an inner fire:

"In her day it was depicted mainly using images linked to space: a certain space was conceived of in which Purgatory was supposed to be located. Catherine, however, did not see purgatory as a scene in the bowels of the earth: for her it is not an exterior but rather an interior fire. This is purgatory: an inner fire."[17]

He further said that:

"'The soul', Catherine says, 'presents itself to God still bound to the desires and suffering that derive from sin and this makes it impossible for it to enjoy the beatific vision of God'.…The soul is aware of the immense love and perfect justice of God and consequently suffers for having failed to respond in a correct and perfect way to this love; and love for God itself becomes a flame, love itself cleanses it from the residue of sin."[48]

In his 2007 encyclical Spe salvi, Pope Benedict XVI, referring to the words of Paul the Apostle in 1 Corinthians 3:12–15 about a fire that both burns and saves, spoke of the opinion that "the fire which both burns and saves is Christ himself, the Judge and Saviour. The encounter with him is the decisive act of judgement. Before his gaze all falsehood melts away.[49]

This encounter with him, as it burns us, transforms and frees us, allowing us to become truly ourselves. All that we build during our lives can prove to be mere straw, pure bluster, and it collapses. Yet in the pain of this encounter, when the impurity and sickness of our lives become evident to us, there lies salvation. His gaze, the touch of his heart heals us through an undeniably painful transformation 'as through fire'. But it is a blessed pain, in which the holy power of his love sears through us like a flame, enabling us to become totally ourselves and thus totally of God.[49]

The pain of love becomes our salvation and our joy.[49]

Duration[edit]

In his 2007 encyclical Spe salvi, Pope Benedict XVI teaches:[49]

It is clear that we cannot calculate the 'duration' of this transforming burning in terms of the chronological measurements of this world. The transforming 'moment' of this encounter eludes earthly time-reckoning – it is the heart's time, it is the time of 'passage' to communion with God in the Body of Christ."[49]

Eastern Catholics[edit]

The popular conceptions of Purgatory that, especially in late medieval times, were common among Catholics of the Latin Church have not necessarily found acceptance in the Eastern Catholic Churches, of which there are 23 in full communion with the Pope. Some have explicitly rejected the notions of punishment by fire in a particular place that are prominent in the popular picture of Purgatory.Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Category handler/data' not found.Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Category handler/data' not found.[<span title="Script error: No such module "delink".">citation needed]

The representatives of the Eastern Orthodox Church at the Council of Florence (1431-1449) argued against these notions, while declaring that they do hold that there is a cleansing after death of the souls of the saved and that these are assisted by the prayers of the living:

"If souls depart from this life in faith and charity but marked with some defilements, whether unrepented minor ones or major ones repented of but without having yet borne the fruits of repentance, we believe that within reason they are purified of those faults, but not by some purifying fire and particular punishments in some place."[50]

The definition of purgatory adopted by that council excluded the two notions with which the Orthodox disagreed and mentioned only the two points that, they said, were part of their faith also. Accordingly, the agreement, known as the Union of Brest, that formalized the admission of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church into the full communion of the Roman Catholic Church stated: "We shall not debate about purgatory, but we entrust ourselves to the teaching of the Holy Church".[51]

Popular notions of purgatory[edit]

Some Catholic saints, theologians and laity have had ideas about purgatory beyond those adopted by the Catholic Church, reflecting or contributing to the popular image, which includes the notions of purification by actual fire, in a determined place and for a precise length of time.

As a place[edit]

In his La naissance du Purgatoire (The Birth of Purgatory), Jacques Le Goff attributes the origin of the idea of a third other-world domain, similar to heaven and hell, called Purgatory, to Paris intellectuals and Cistercian monks at some point in the last three decades of the twelfth century, possibly as early as 1170−1180.[52] Previously, the Latin adjective purgatorius, as in purgatorius ignis (cleansing fire) existed, but only then did the noun purgatorium appear, used as the name of a place called Purgatory.[6]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". Robert Bellarmine also taught "that Purgatory, at least the ordinary place of expiation, is situated in the interior of the earth, that the souls in Purgatory and the reprobate are in the same subterranean space in the deep abyss which the Scripture calls Hell."[53][54]

The change happened at about the same time as the composition of the book Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii, an account by an English Cistercian of a penitent knight's visit to the land of Purgatory reached through a cave in the island known as Station Island or St Patrick's Purgatory in the lake of Lough Derg, County Donegal, Ireland. Le Goff said this book "occupies an essential place in the history of Purgatory, in whose success it played an important, if not decisive, role".[6]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

One of the earliest depictions of St Patrick's Purgatory is a fresco in the Convent of San Francisco in Todi, Umbria, Italy.[55][56] Whitewashed long ago, this fresco was only restored in 1976. The painter was likely Jacopo di Mino del Pellicciaio, and the date of the fresco is around 1345. Purgatory is shown as a rocky hill filled with separate openings into its hollow center. Above the mountain St Patrick introduces the prayers of the faithful that can help attenuate the sufferings of the souls undergoing purification. In each opening, sinners are tormented by demons and by fire. Each of the seven deadly sins – avarice, envy, sloth, pride, anger, lust, and gluttony – has its own region of purgatory and its own appropriate tortures.

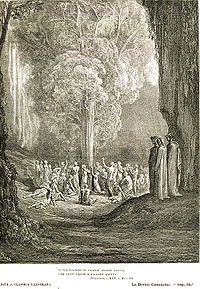

Le Goff dedicates the final chapter of his book to the Purgatorio, the second canticle of the Divine Comedy, a poem by fourteenth-century Italian author Dante Alighieri. In an interview Le Goff declared: "Dante's Purgatorio represents the sublime conclusion of the slow development of Purgatory that took place in the course of the Middle Ages. The power of Dante's poetry made a decisive contribution to fixing in the public imagination this 'third place', whose birth was on the whole quite recent."[57] Dante pictures Purgatory as an island at the antipodes of Jerusalem, pushed up, in an otherwise empty sea, by the displacement caused by the fall of Satan, which left him fixed at the central point of the globe of the Earth. The cone-shaped island has seven terraces on which souls are cleansed from the seven deadly sins or capital vices as they ascend. Additional spurs at the base hold those for whom beginning the ascent is delayed because in life they were excommunicates indolent or late repenters. At the summit is the Garden of Eden, from where the souls, cleansed of evil tendencies and made perfect, are taken to heaven.

The Catholic Church has included in its teaching the idea of a purgatory rather as a condition than a place. On 4 August 1999, Pope John Paul II, speaking of purgatory, said: "The term does not indicate a place, but a condition of existence. Those who, after death, exist in a state of purification, are already in the love of Christ who removes from them the remnants of imperfection as "a condition of existence".[16]

Fire[edit]

Fire has an important place in the popular image of purgatory and has been the object of speculation by theologians, speculation to which the article on purgatory in the Catholic Encyclopedia relates the warning by the Council of Trent against "difficult and subtle questions which tend not to edification."[58]

Fire has never been included in the Catholic Church's defined doctrine on purgatory, but speculation about it is traditional. "The tradition of the Church, by reference to certain texts of Scripture, speaks of a cleansing fire."[59] In this regard the Catechism of the Catholic Church references in particular two New Testament passages: "If anyone's work is burned up, he will suffer loss, though he himself will be saved, but only as through fire"[60] and "so that the tested genuineness of your faith—more precious than gold that perishes though it is tested by fire—may be found to result in praise and glory and honor at the revelation of Jesus Christ".[61] Catholic theologians have also cited verses such as "I will put this third into the fire, and refine them as one refines silver, and test them as gold is tested. They will call upon my name, and I will answer them. I will say, 'They are my people'; and they will say, 'The LORD is my God'",[62] a verse that the Jewish school of Shammai applied to God's judgment on those who are not completely just nor entirely evil.[63][64]

Use of the image of a purifying fire goes back as far as Origen who, with reference to 1 Corinthians 3:10–15, seen as referring to a process by which the dross of lighter transgressions will be burnt away, and the soul, thus purified, will be saved,[58][65] wrote:

"Suppose you have built, after the foundation which Christ Jesus has taught, not only gold, silver, and precious stones − if indeed you possess gold and much silver or little − suppose you have silver, precious stones, but I say not only these elements, but suppose that you have also wood and hay and stubble, what does he wish you to become after your final departure? To enter afterwards then into the holy lands with your wood and with your hay and stubble so that you may defile the Kingdom of God? But again do you want to be left behind in the fire on account of the hay, the wood, the stubble, and to receive nothing due you for the gold and the silver and precious stone? That is not reasonable. What then? It follows that you receive the fire first due to the wood, and the hay and the stubble. For to those able to perceive, our God is said to be in reality a consuming fire."[66]

Origen also speaks of a refining fire melting away the lead of evil deeds, leaving behind only pure gold.[67]

Augustine tentatively put forward the idea of a post-death purgatorial fire for some Christian believers:

"69. It is not incredible that something like this should occur after this life, whether or not it is a matter for fruitful inquiry. It may be discovered or remain hidden whether some of the faithful are sooner or later to be saved by a sort of purgatorial fire, in proportion as they have loved the goods that perish, and in proportion to their attachment to them."[68]

Gregory the Great also argued for the existence, before Judgment, of a purgatorius ignis (a cleansing fire) to purge away minor faults (wood, hay, stubble) not mortal sins (iron, bronze, lead).[69] Pope Gregory, in the Dialogues, quotes Christ's words (in Mat 12:32) to establish purgatory:

"But yet we must believe that before the day of judgment there is a purgatory fire for certain small sins: because our Saviour saith, that he which speaketh blasphemy against the holy Ghost, that it shall not be forgiven him, neither in this world, nor in the world to come. (Mat 12:32) Out of which sentence we learn, that some sins are forgiven in this world, and some other may be pardoned in the next: for that which is denied concerning one sin, is consequently understood to be granted touching some other."[70]

Gregory of Nyssa several times spoke of purgation by fire after death,[71] but he generally has apocatastasis in mind.[72]

Medieval theologians accepted the association of purgatory with fire. Thus the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas considered it probable that Purgatory was situated close to hell, so that the same fire that tormented the damned cleansed the just souls in Purgatory.[73]

Ideas about the supposed fire of purgatory have changed with time: in the early 20th century the Catholic Encyclopedia reported that, while in the past most theologians had held that the fire of purgatory was in some sense a material fire, though of a nature different from ordinary fire, the view of what then seemed to be the majority of theologians was that the term was to be understood metaphorically.[74][75]

Depictions[edit]

-

Purgatory, by Peter Paul Rubens. Top: Trinity, with Mary; Middle: Angels; Lower: purified souls being pulled up towards heaven; Bottom: souls in non-fiery purgation

-

Altar in Iglesia de la Concepción, Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Top: Trinity; Mid-top: Mary, John the Baptist, Holy family; Mid: archangel Michael; Lower: Saints interceding; Bottom: souls undergoing fiery purgation, still with worldly attachments (shackles) and venial sins (snakes).

-

A fiery purgatory in the Très riches heures du Duc de Berry. The faithful dead (bottom left) go through the furnace and once purified (top right) ascend towards Heaven. Some of the faithful are plucked by angels, the result of intercessory prayers. The icy water is a common pairing.

-

Our Lady Interceding for the Souls in Purgatory, by Andrea Vaccaro. Top-right: Christ granting; Middle-left: Mary interceding; Bottom-right: purged souls capable of focus on Christ; Bottom-left: indistinct souls undergoing non-fiery purgation.

-

Our Lady of Mount Carmel and purgatory, Beniaján, Spain

-

Our Lady of Mount Carmel and purgatory, North End, Boston

-

Our Lady, St Monica and souls in purgatory, Rattenberg, Tyrol

-

Our Lady of Passau in St Felix Church, Kientzheim, Alsace

-

Purgatory, 1419 drawing by unknown artist from Strasbourg

-

Painting by Michel Serre in the Saint Cannat Church, Marseilles

-

Altar predella in the town church of Bad Wimpfen, Baden-Württemberg

-

Request for prayer for the souls in purgatory

-

Stained-glass window in Puerto Rico Cathedral

-

Purgatory by Venezuelan painter Cristóbal Rojas (1890)

-

Miniature by Stefan Lochner showing souls in purgatory

Eastern Orthodoxy[edit]

While the Eastern Orthodox Church rejects the term Purgatory, it acknowledges an intermediate state after death and before final judgment, and offers prayer for the dead. According to the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America:

The moral progress of the soul, either for better or for worse, ends at the very moment of the separation of the body and soul; at that very moment the definite destiny of the soul in the everlasting life is decided. ...There is no way of repentance, no way of escape, no reincarnation and no help from the outside world. Its place is decided forever by its Creator and judge. The Orthodox Church does not believe in Purgatory (a place of purging), that is the inter-mediate state after death in which the souls of the saved (those who have not received temporal punishment for their sins) are purified of all taint preparatory to entering into Heaven, where every soul is perfect and fit to see God. Also, the Orthodox Church does not believe in indulgences as remissions from purgatorial punishment. Both purgatory and indulgences are inter-corelated theories, unwitnessed in the Bible or in the Ancient Church, and when they were enforced and applied they brought about evil practices at the expense of the prevailing Truths of the Church. If Almighty God in His merciful loving-kindness changes the dreadful situation of the sinner, it is unknown to the Church of Christ. The Church lived for fifteen hundred years without such a theory.[76]

Eastern Orthodox teaching is that, while all undergo an individual judgment immediately after death, neither the just nor the wicked attain the final state of bliss or punishment before the Last Day,[77] with some exceptions for righteous souls like the Theotokos (Blessed Virgin Mary), "who was borne by the angels directly to heaven."[78]

The Eastern Orthodox Church holds that it is necessary to believe in this intermediate after-death state in which souls are perfected and brought to full divinization, a process of growth rather than of punishment, which some Orthodox have called purgatory.[79] Eastern Orthodox theology does not generally describe the situation of the dead as involving suffering or fire, although it nevertheless describes it as a "direful condition".[80] The souls of the righteous dead are in light and rest, with a foretaste of eternal happiness; but the souls of the wicked are in a state the reverse of this. Among the latter, such souls as have departed with faith but "without having had time to bring forth fruits worthy of repentance ... may be aided towards the attainment of a blessed resurrection [at the end of time] by prayers offered in their behalf, especially those offered in union with the oblation of the bloodless sacrifice of the Body and Blood of Christ, and by works of mercy done in faith for their memory."[81]

The state in which souls undergo this experience is often referred to as "Hades".[82]

The Orthodox Confession of Peter Mogila (1596–1646), adopted, in a Greek translation by Meletius Syrigos, by the 1642 Council of Jassy in Romania, professes that "many are freed from the prison of hell ... through the good works of the living and the Church's prayers for them, most of all through the unbloody sacrifice, which is offered on certain days for all the living and the dead" (question 64); and (under the heading "How must one consider the purgatorial fire?") "the Church rightly performs for them the unbloody sacrifice and prayers, but they do not cleanse themselves by suffering something. The Church never maintained that which pertains to the fanciful stories of some concerning the souls of their dead who have not done penance and are punished, as it were, in streams, springs and swamps." (question 66).[83]

The Eastern Orthodox Synod of Jerusalem (1672) declared:

"The souls of those that have fallen asleep are either at rest or in torment, according to what each hath wrought" (an enjoyment or condemnation that will be complete only after the resurrection of the dead); but the souls of some "depart into Hades, and there endure the punishment due to the sins they have committed. But they are aware of their future release from there, and are delivered by the Supreme Goodness, through the prayers of the Priests and the good works which the relatives of each do for their Departed, especially the unbloody Sacrifice benefiting the most, which each offers particularly for his relatives that have fallen asleep and which the Catholic and Apostolic Church offers daily for all alike. Of course, it is understood that we do not know the time of their release. We know and believe that there is deliverance for such from their direful condition, and that before the common resurrection and judgment, but when we know not."[80]

Some Orthodox believe in a teaching of "aerial toll-houses" for the souls of the dead. According to this theory, which is rejected by other Orthodox but appears in the hymnology of the church,[84] "following a person's death the soul leaves the body and is escorted to God by angels. During this journey the soul passes through an aerial realm which is ruled by demons. The soul encounters these demons at various points referred to as 'toll-houses' where the demons then attempt to accuse it of sin and, if possible, drag the soul into hell."[85]

Some early patristic theologians of the Eastern Church taught and believed in "apocatastasis", the belief that all creation would be restored to its original perfect condition after a remedial purgatorial reformation. Clement of Alexandria was one of the early church theologians who taught this view.

Protestantism[edit]

In general, Protestant churches reject the Catholic doctrine of purgatory although some teach the existence of an intermediate state, which is termed Hades.[86][87][88] However, Protestant churches that affirm the existence of an intermediate state (Hades) reject the Roman Catholic view that it is a place of purgation.[88] Affirming the existence of an intermediate state, adherents of certain Protestant denominations, such as those of the Lutheran Churches, say prayers for the dead.[89][90]

Reformed Protestants, consistent with the views of John Calvin, hold that a person enters into the fullness of one's bliss or torment only after the resurrection of the body, and that the soul in that interim state is conscious and aware of the fate in store for it.[91] Others, such as the Seventh-day Adventist Church, have held that souls in the intermediate state between death and resurrection are without consciousness, a state known as soul sleep.[92][93]

The general Protestant view is that the biblical canon, from which Protestants exclude deuterocanonical books such as 2 Maccabees (though this book is included in traditional Protestant Bibles in the intertestamental Apocrypha section), contains no overt, explicit discussion of purgatory as taught in the Roman Catholic sense, and therefore it should be rejected as an unbiblical belief.[94]

The reality of purgatorial purification is envisaged in Thomas Talbott's The Inescapable Love of God[95] Different views are expressed by different theologians in two different editions of Four Views of Hell.[96]

Lutheranism[edit]

The Lutheran Churches teach the existence of an intermediate state after the departure of the soul from the body, until the time of the Last Judgment.[88] This intermediate state, known as Hades, is divided into two chambers: (1) Paradise for the righteous (2) Gehenna for the wicked.[88] Unlike the Roman Catholic doctrine of purgatory, the Lutheran doctrine of Hades is not a place of purgation.[88]

Beside, the divine narrative informs us, that there is an impassable gulf, dividing Hades into two apartments. And so great is this chasm as to render it impossible to pass from one apartment to the other. And, therefore, as this rich man and Lazarus are not on the same side of the gulf, they are not in the same place. They are both in Hades, but not the same apartment of it. The apartment to which the rich man went, the Scriptures call Γέεννα hell; and that to which Lazarus went, they call PARADISE, Abraham's bosom, Paradise, heaven. And, therefore, inasmuch as all spirits, upon hearing their sentence, must pass away into one of these apartments, it is conclusive, that the good will go to where Lazarus and the dying thief are, with Jesus in ουρανός, heaven, which is in Hades; and the bad will go where the rich man is in Γέεννα, hell, also in Hades. So that the spirit, after its departure from the body, after hearing its doom, and upon the execution of the sentence, enters immediately into Hades, either to a state and place of suffering or of enjoyment. And here, in Hades, the righteous enjoy bliss, such as 'eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, not the heart of man conceived.' But the wicked experience miseries such as are represented by the gnawings of "the worm that never dies," and burnings of "the fire that is never quenched." But once more: the state of spirits in Hades, between death and judgment, is not one of probation, nor yet or purgation.[88]

The Protestant Reformer Martin Luther was once recorded as saying:[97]

As for purgatory, no place in Scripture makes mention thereof, neither must we any way allow it; for it darkens and undervalues the grace, benefits, and merits of our blessed, sweet Saviour Christ Jesus. The bounds of purgatory extend not beyond this world; for here in this life the upright, good, and godly Christians are well and soundly scoured and purged.

In his 1537 Smalcald Articles, Luther stated:[98]

Therefore purgatory, and every solemnity, rite, and commerce connected with it, is to be regarded as nothing but a specter of the devil. For it conflicts with the chief article [which teaches] that only Christ, and not the works of men, are to help [set free] souls. Not to mention the fact that nothing has been [divinely] commanded or enjoined upon us concerning the dead.

With respect to the related practice of praying for the dead, Luther stated:[99]

As for the dead, since Scripture gives us no information on the subject, I regard it as no sin to pray with free devotion in this or some similar fashion: “Dear God, if this soul is in a condition accessible to mercy, be thou gracious to it.” And when this has been done once or twice, let it suffice. (Confession Concerning Christ’s Supper, Vol. XXXVII, 369)[99]

A core statement of Lutheran doctrine, from the Book of Concord, states: "We know that the ancients speak of prayer for the dead, which we do not prohibit; but we disapprove of the application ex opere operato of the Lord's Supper on behalf of the dead. ... Epiphanius [of Salamis] testifies that Aerius [of Sebaste] held that prayers for the dead are useless. With this he finds fault. Neither do we favor Aerius, but we do argue with you because you defend a heresy that clearly conflicts with the prophets, apostles, and Holy Fathers, namely, that the Mass justifies ex opere operato, that it merits the remission of guilt and punishment even for the unjust, to whom it is applied, if they do not present an obstacle." (Philipp Melanchthon, Apology of the Augsburg Confession).[100] High Church Lutheranism, like Anglo-Catholicism, is more likely to accept some form of purgatory.Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Category handler/data' not found.Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Category handler/data' not found.[<span title="Script error: No such module "decodeEncode".">citation needed] Lutheran Reformer Mikael Agricola still believed in the basic beliefs of purgatory.[101] Purgatory as such is not mentioned at all in the Augsburg Confession, which claims that "our churches dissent in no article of the faith from the Church Catholic, but only omit some abuses which are new."[102]

Anglicanism[edit]

Anglicans, as with other Reformed Churches, historically teach that the saved undergo the process of glorification after death.[103] This process has been compared by Jerry L. Walls and James B. Gould with the process of purification in the core doctrine of purgatory (see Reformed, below).

Purgatory was addressed by both of the "foundation features" of Anglicanism in the 16th century: the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion and the Book of Common Prayer.[104]

Article XXII of the Thirty-Nine Articles states that "The Romish Doctrine concerning Purgatory . . . is a fond thing, vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God."[105] Prayers for the departed were deleted from the 1552 Book of Common Prayer because they suggested a doctrine of purgatory.

The 19th century Anglo-Catholic revival led to restoring prayers for the dead.[106] John Henry Newman, in his Tract XC of 1841 §6, discussed Article XXII. He highlighted the fact that it is the "Romish" doctrine of purgatory coupled with indulgences that Article XXII condemns as "repugnant to the Word of God." The article did not condemn every doctrine of purgatory and it did not condemn prayers for the dead.[107]

Shortly before becoming a Roman Catholic,[108] John Henry Newman argued that the essence of the doctrine is locatable in ancient tradition, and that the core consistency of such beliefs is evidence that Christianity was "originally given to us from heaven".[109]

As of the year 2000, the state of the doctrine of purgatory in Anglicanism was summarized as follows:

Purgatory is seldom mentioned in Anglican descriptions or speculations concerning life after death, although many Anglicans believe in a continuing process of growth and development after death.[110]

Anglican Bishop John Henry Hobart (1775–1830) wrote that "Hades, or the place of the dead, is represented as a spacious receptacle with gates, through which the dead enter."[111] The Anglican Catechist of 1855 elaborated on Hades, stating that it "is an intermediate state between death and the resurrection, in which the soul does not sleep in unconsciousness, but exists in happiness or misery till the resurrection, when it shall be reunited to the body and receive its final reward."[112] This intermediate state includes both Paradise and Gehenna, "but with an impassable gulf between the two".[21] Souls remain in Hades until the Final Judgment and "Christians may also improve in holiness after death during the middle state before the final judgment."[113]

Leonel L. Mitchell (1930–2012) offers this rationale for prayers for the dead:

No one is ready at the time of death to enter into life in the nearer presence of God without substantial growth precisely in love, knowledge, and service; and the prayer also recognizes that God will provide what is necessary for us to enter that state. This growth will presumably be between death and resurrection."[114]

Anglican theologian C. S. Lewis (1898–1963), reflecting on the history of the doctrine of purgatory in the Anglican Communion, said there were good reasons for "casting doubt on the 'Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory' as that Romish doctrine had then become" not merely a "commercial scandal" but also the picture in which the souls are tormented by devils, whose presence is "more horrible and grievous to us than is the pain itself," and where the spirit who suffers the tortures cannot, for pain, "remember God as he ought to do." Lewis believed instead in purgatory as presented in John Henry Newman's The Dream of Gerontius. By this poem, Lewis wrote, "Religion has reclaimed Purgatory," a process of purification that will normally involve suffering.[115] Lewis's allegory The Great Divorce (1945) considered a version of purgatory in the related idea of a "refrigidarium", the opportunity for souls to visit a lower region of heaven and choose to be saved, or not.

Methodism[edit]

Methodist churches, in keeping with Article XIV - Of Purgatory in the Articles of Religion, hold that "the Romish doctrine concerning purgatory ... is a fond thing, vainly invented, and grounded upon no warrant of Scripture, but repugnant to the Word of God."[116] However, in traditional Methodism, there is a belief in Hades, "the intermediate state of souls between death and the general resurrection," which is divided into Paradise (for the righteous) and Gehenna (for the wicked).[117][86] After the general judgment, Hades will be abolished.[86] John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, "made a distinction between hell (the receptacle of the damned) and Hades (the receptacle of all separate spirits), and also between paradise (the antechamber of heaven) and heaven itself."[118][119] The dead will remain in Hades "until the Day of Judgment when we will all be bodily resurrected and stand before Christ as our Judge. After the Judgment, the Righteous will go to their eternal reward in Heaven and the Accursed will depart to Hell (see Matthew 25)."[120]

Reformed[edit]

After death, Reformed theology teaches that through glorification, God "not only delivers His people from all their suffering and from death, but delivers them too from all their sins."[24] In glorification, Reformed Christians believe that the departed are "raised and made like the glorious body of Christ".[24] Theologian John F. MacArthur has written that "nothing in Scripture even hints at the notion of purgatory, and nothing indicates that our glorification will in any way be painful."[121]

Walls' argument[edit]

Jerry L. Walls and James B. Gould have likened the glorification process to the core or sanctification view of purgatory[122] "Grace is much more than forgiveness, it is also transformation and sanctification, and finally, glorification. We need more than forgiveness and justification to purge our sinful dispositions and make us fully ready for heaven. Purgatory is nothing more than the continuation of the sanctifying grace we need, for as long as necessary to complete the job".[123]

As an argument for the existence of purgatory, Protestant religious philosopher Jerry L. Walls[124] wrote Purgatory: The Logic of Total Transformation (2012). He lists some "biblical hints of purgatory" (Mal 3:2; 2 Mac 12:41–43; Mat 12:32; 1 Cor 3:12-15) that helped give rise to the doctrine,[125] and finds its beginnings in early Christian writers whom he calls "Fathers and Mothers of Purgatory".[126] Citing Le Goff, he sees the 12th century as that of the "birth of purgatory", arising as "a natural development of certain currents of thought that had been flowing for centuries",[127] and the 13th century at that of its rationalization, "purging it of its offensive popular trappings", leading to its definition by a council as the church's doctrine in 1274.[128]

Walls does not base his belief in purgatory primarily on scripture, the Mothers and Fathers of the Church, or the magisterium (doctrinal authority) of the Catholic Church. Rather his basic argument is that, in a phrase he often uses, it "makes sense."[129] For Walls, purgatory has a logic, as in the title of his book. He documents the "contrast between the satisfaction and sanctification models" of purgatory. In the satisfaction model, "the punishment of purgatory" is to satisfy God's justice. In the sanctification model, Wall writes: "Purgatory might be pictured ... as a regimen to regain one’s spiritual health and get back into moral shape."[130]

In Catholic theology Walls claims that the doctrine of purgatory has "swung" between the "poles of satisfaction and sanctification" sometimes "combining both elements somewhere in the middle". He believes the sanctification model "can be affirmed by Protestants without in any way contradicting their theology" and that they may find that it "makes better sense of how the remains of sin are purged" than an instantaneous cleansing at the moment of death.[131]

Latter-day Saint Movement[edit]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, teaches of an intermediate place for spirits between their death and their bodily resurrection. This place, called "the spirit world," includes "paradise" for the righteous and "prison" for those who do not know God. Spirits in paradise serve as missionaries to the spirits in prison, who can still accept salvation. In this sense, spirit prison can be conceptualized as a type of Purgatory. In addition to hearing the message from the missionary spirits, the spirits in prison can also accept posthumous baptism and other posthumous ordinances performed by living church members in temples on Earth. This is frequently referred to as "baptism for the dead" and "temple work."[132] Members of the church believe that during the three days following Christ's crucifixion, he organized spirits in paradise and commissioned them to preach to the spirits in prison.[133]

Analogous concepts in other religions[edit]

Judaism[edit]

In Judaism, Gēʾ-Hīnnōm is a place of purification where, according to some traditions, most sinners spend up to a year before release.

The view of Purgatory can be found in the teaching of the Shammaites: "In the last judgment day there shall be three classes of souls: the righteous shall at once be written down for the life everlasting; the wicked, for Gehenna; but those whose virtues and sins counterbalance one another shall go down to Gehenna and float up and down until they rise purified; for of them it is said: 'I will bring the third part into the fire and refine them as silver is refined, and try them as gold is tried' [Zech. xiii. 9.]; also, 'He [the Lord] bringeth down to Sheol and bringeth up again'" (I Sam. ii. 6). The Hillelites seem to have had no purgatory; for they said: "He who is 'plenteous in mercy' [Ex. xxxiv. 6.] inclines the balance toward mercy, and consequently the intermediates do not descend into Gehenna" (Tosef., Sanh. xiii. 3; R. H. 16b; Bacher, "Ag. Tan." i. 18). Still they also speak of an intermediate state.

Regarding the time which Purgatory lasts, the accepted opinion of R. Akiba is twelve months; according to R. Johanan b. Nuri, it is only forty-nine days. Both opinions are based upon Isa. lxvi. 23–24: "From one new moon to another and from one Sabbath to another shall all flesh come to worship before Me, and they shall go forth and look upon the carcasses of the men that have transgressed against Me; for their worm shall not die, neither shall their fire be quenched"; the former interpreting the words "from one new moon to another" to signify all the months of a year; the latter interpreting the words "from one Sabbath to another," in accordance with Lev. xxiii. 15–16, to signify seven weeks. During the twelve months, declares the baraita (Tosef., Sanh. xiii. 4–5; R. H. 16b), the souls of the wicked are judged, and after these twelve months are over they are consumed and transformed into ashes under the feet of the righteous (according to Mal. iii. 21 [A. V. iv. 3]), whereas the great seducers and blasphemers are to undergo eternal tortures in Gehenna without cessation (according to Isa. lxvi. 24).

The righteous, however, and, according to some, also the sinners among the people of Israel for whom Abraham intercedes because they bear the Abrahamic sign of the covenant are not harmed by the fire of Gehenna even when they are required to pass through the intermediate state of purgatory ('Er. 19b; Ḥag. 27a).[134]

Maimonides declares, in his 13 principles of faith, that the descriptions of Gehenna, as a place of punishment in rabbinic literature, were pedagocically motivated inventions to encourage respect of the Torah commandments by mankind, which had been regarded as immature.[135] Instead of being sent to Gehenna, the souls of the wicked would actually get annihilated.[136]

Mandaeism[edit]

In Mandaean cosmology, the soul must go through multiple maṭarta (i.e., purgatories, watch-stations, or toll-stations) after death before finally reaching the World of Light ("heaven").[137]

The Mandaeans believe in purification of souls inside of Leviathan,[138] whom they also call Ur.[139]

Islam[edit]

Al-A'raf has similarities to purgatory. In this way, Al-A'raf is a more analogous concept to Christian Purgatory.

Jahannam refers to hellfire as well as hell as a location itself;[140] [141]

Some scholars asserted by referring to God's mercy (r-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi) that hell will eventually end. This doctrine is referred to as fana' al-nar ('annihilation of fire'). However, this doctrine is not universally accepted in Islam and rejected by the majority.[142]

Hinduism[edit]

While Hell in Hinduism is not typically considered to be a central feature of the religion, it does exist. Hell for Hindus involves the realm of naraka. Naraka is not a permanent place for the soul after death, but a realm related to "punishment for moral impure deeds." It functions more like a prison than the Hell of, for instance, traditional Christianity.[143]

There are a few different views of naraka in Hinduism. One of these, discussed in the Mahābhārata, holds that one goes from naraka's punishment straight to heaven (svarga) in their next life, though this celestial realm is distinct from the ultimate form of salvation in Hinduism: spiritual liberation from the cycle of rebirth known as mokṣa. Another view is that after naraka, one would then proceed to be reborn as an animal and just continue the cycle of rebirth.[143]

Zoroastrianism[edit]

According to Zoroastrian eschatology, the wicked will get purified in molten metal.[144]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ "Purgatory", Oxford English Dictionary

- ↑ 2.0 2.1

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Purgatory in Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ "purgatory definition – English definition dictionary – Reverso". dictionary.reverso.net. Archived from the original on 2007-09-12. Retrieved 2007-12-20. - "a place or condition of suffering or torment, esp. one that is temporary"

- ↑ Cassell's Latin Dictionary, Marchant, J.R.V, & Charles, Joseph F., (Eds.), Revised Edition, 1928, p.456

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4

- ↑ Megan McLaughlin, Consorting with Saints: Prayer for the Dead in Early Medieval France (Cornell University Press 1994 ISBN 978-0-8014-2648-3), p. 18

- ↑ Cf.2 Maccabees 12:42–45

- ↑ Waterworth, J. (ed.). "The Council of Trent, Decree concerning the Canonical Scriptures". Hanover Historical Texts Project. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Council of Trent. "Decree concerning the Canonical Scriptures". EWTN. Archived from the original on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ "2 Maccabees, chapter 12". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. www.usccb.org. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ↑ Robert Osei-Bonsu, "Purgatory: A Study of the Historical Development and Its Compatibility with the Biblical Teaching on the Afterlife" in Philosophy Study, ISSN 2159-5313 April 2012, Vol. 2, No. 4, p. 291

- ↑ Karen Hartnup, 'On the Beliefs of the Greeks': Leo Allatios and Popular Orthodoxy (Brill 2004), p. 2008

- ↑

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "4 August 1999 – John Paul II". www.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Saint Catherine of Genoa . Benedict XVI General Audience, January 12, 2011, accessed May 15, 2018

- ↑ "Articles of Religion, article XXII". Archived from the original on 2019-02-27. Retrieved 2019-02-26.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ 21.0 21.1

- ↑

- ↑ Olivier Clément, L'Église orthodoxe. Presses Universitaires de France, 2006, Section 3, IV

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "Glorification". Protestant Reformed Churches in America. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ↑ "Browse by Subject". Archived from the original on 2008-01-13. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1030–1031". www.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ "Is purgatory a physical place?". Catholic Answers. Retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church - IntraText". www.vatican.va. 1030-32. Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- ↑ [Denzinger 856; original text in Latin: "Quod si vere paenitentes ..."

- ↑ Denzinger 1304]; original text in Latin: "Item, si vere paenitentes ..."

- ↑ "First speech by Mark, Archbishop of Ephesus, on the purifying fire" in Patrologia Orientalis, vol. 15, pp. 40–41

- ↑ Denzinger 1820; original text in Latin: "Cum catholica Ecclesia, Spiritu Sancto edocta, ..."

- ↑ Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, 210–211

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1030–1032". Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Churchm 1054". Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1472−1473". Archived from the original on 2013-03-06. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church 958

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church 1032

- ↑ "CCC 1054". Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1855−1861". Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1472". Archived from the original on 2013-03-06. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "CCC 1863". Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑

- ↑ Jack Mulder, Kierkegaard and the Catholic Tradition: Conflict and Dialogue (Indiana University Press 2010 ISBN 978-0-25335536-2), pp. 182–183

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1475". Archived from the original on 2013-03-06. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1478". Archived from the original on 2013-03-06. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ Quoted in Benedict J. Groeschel, A Still, Small Voice (Ignatius Press 1993 ISBN 978-0-89870436-5

- ↑ "Pope Benedict XVI, General Audience of 12 January 2011". Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 Encyclical Spe salvi , 46–47].

- ↑ "First Speech by Mark, Archbishop of Ephesus, on Purifying Fire" in Patrologia Orientalis, vol. 15, pp. 40–41

- ↑ "Treaty of Brest, Article 5". Archived from the original on 2007-08-30. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ↑ Though a place in which "space and time were different in Purgatory than space and time here below-governed by different rules" and "marvelous".[6]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

- ↑ Catech. Rom., chap. vi. § 1.

- ↑

- ↑ "Station Island". Creature and Creator. 26 November 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-09-18. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ↑ MacTréinfhir, N. (1986). The Todi Fresco and St. Patrick's Purgatory, Lough Derg. Clogher Record, 12, 141-158.

- ↑ "Fabio Gambaro, "L'invenzione del purgatorio" in La Repubblica, 27 September 2005". 27 September 2005. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Catholic Encyclopedia: Purgatory". www.newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 2005-09-04. Retrieved 2005-09-11.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1031". Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 3:15

- ↑ 1 Peter 1:7

- ↑ Zechariah 13:9

- ↑

- ↑ "Edward P. Saunders, "Do we know what happens in Purgatory? Is there really a fire?"". 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2019-01-03. Retrieved 2019-01-02.

- ↑ Smith, Scott. "Where is Purgatory in the Bible?". All Roads Lead to Rome. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ Origen, Homily 16, in Homilies on Jeremiah and 1 Kings 28 (CUA Press 1998), pp. 173−174; original text: Patrologia graeca, vol. 13, col. 415 C−D

- ↑

- ↑ "St. Augustine, Enchiridion: On Faith, Hope, and Love (1955). English translation".

- ↑ "Gregory the Great, Dialogues, book IV, chapter 39" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-05-24. Retrieved 2012-11-15.

- ↑ "Gregory the Great, Dialogues (1911) Book 4. Pp. 177-258".

- ↑ "When he has quitted his body and the difference between virtue and vice is known he cannot approach God till the purging fire shall have cleansed the stains with which his soul was infested. That same fire in others will cancel the corruption of matter, and the propensity to evil" (Gregory of Nyssa, Sermon on the Dead, pp. 13:445, 448)

- ↑

- ↑ "Summa Theologica, appendix 2, article 2: "Whether it is the same place where souls are cleansed, and the damned punished?"". Archived from the original on 2019-01-03. Retrieved 2019-01-02.

- ↑ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Hell". www.newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 2018-01-23. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Purgatory". www.newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 2021-10-26. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- ↑ "Death, the Threshold to Eternal Life – Liturgy & Worship – Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America". www.goarch.org. Archived from the original on 2010-06-12. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ↑ John Meyendorff, Byzantine Theology (London: Mowbrays, 1974) pp. 220–221. "At death man's body goes to the earth from which it was taken, and the soul, being immortal, goes to God, who gave it. The souls of men, being conscious and exercising all their faculties immediately after death, are judged by God. This judgment following man's death we call the Particular Judgment. The final reward of men, however, we believe will take place at the time of the General Judgment. During the time between the Particular and the General Judgment, which is called the Intermediate State, the souls of men have foretaste of their blessing or punishment" (The Orthodox Faith ).

- ↑ Michael Azkoul, What Are the Differences Between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism?

- ↑ Ted A. Campbell, Christian Confessions: a Historical Introduction (Westminster John Knox Press 1996 ISBN 0-664-25650-3), p. 54

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Dennis Bratcher (ed.). "The Confession of Dositheus". Archived from the original on 2009-02-21. Decree 18

- ↑ Catechism of St. Philaret of Moscow , 372 and 376; Constas H. Demetry, Catechism of the Eastern Orthodox Church p. 37; John Meyendorff, Byzantine Theology (London: Mowbrays, 1974) p. 96; cf. "The Orthodox party ... remarked that the words quoted from the book of Maccabees, and our Saviour's words, can only prove that some sins will be forgiven after death" (OrthodoxInfo.com, The Orthodox Response to the Latin Doctrine of Purgatory )

- ↑ What Are the Differences Between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism? ; Constas H. Demetry, Catechism of the Eastern Orthodox Church p. 37

- ↑ Orthodox Confession of Faith, questions 64–66.

- ↑ In both the Greek and Slavonic Euchologion, in the canon for the departure of the soul by St. Andrew, we find in Ode 7: "All holy angels of the Almighty God, have mercy upon me and save me from all the evil toll-houses" (Evidence for the Tradition of the Toll Houses found in the Universally Received Tradition of the Church). "When my soul is about to be forcibly parted from my body's limbs, then stand by my side and scatter the counsels of my bodiless foes and smash the teeth of those who implacably seek to swallow me down, so that I may pass unhindered through the rulers of darkness who wait in the air, O Bride of God" (Octoechos, Tone Two, Friday Vespers). "Pilot my wretched soul, pure Virgin, and have compassion on it, as it slides under a multitude of offences into the deep of destruction; and at the fearful hour of death snatch me from the accusing demons and from every punishment" (Ode 6, Tone 1 Midnight Office for Sunday).

- ↑ "Saint Luke the Evangelist Orthodox Church is a Chicago Parish of the Orthodox Church in America located in Palos Hills, Illinois". www.stlukeorthodox.com. Archived from the original on 2016-11-06. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2

- ↑

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 88.3 88.4 88.5

- ↑ "Defense of the Augsburg Confession - Book of Concord". bookofconcord.org. Archived from the original on 2015-10-26. Retrieved 2015-09-22.

we know that the ancients speak of prayer for the dead, which we do not prohibit

- ↑ Futrell, Richard (6 September 2014). "Prayers for the Dead: A Scriptural and Lutheran Worldview". Shepherd of the Hills Lutheran Church (Missouri Synod). Retrieved 3 November 2023.

The historic practice within the Lutheran Church had prayers for the dead in their Prayer of the Church. For example, if we were to look at a typical Lutheran service during Luther's lifetime, we would find in the Prayer of the Church not only intercessions, special prayers, and the Lord's Prayer, which are still typical today in Lutheran worship, but also prayers for the dead.

- ↑ John Calvin wrote: "As long as (our spirit) is in the body it exerts its own powers; but when it quits this prison-house it returns to God, whose presence it meanwhile enjoys, while it rests in the hope of a blessed Resurrection. This rest is its paradise. On the other hand, the spirit of the reprobate, while it waits for the dreadful judgment, is tortured by that anticipation" (Psychopannychia by John Calvin)

- ↑

- ↑ Martin Luther, contending against the doctrine of purgatory, spoke of the souls of the dead as quite asleep, but this notion of unconscious soul sleep is not included in the Lutheran Confessions and Lutheran theologians generally reject it. (See Soul Sleep – Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod.)

- ↑ Robert L. Millet, By what Authority?: The Vital Question of Religious Authority in Christianity (Mercer University, 2010), 66.

- ↑

- ↑ John F. Walvoord, Zachary J. Hayes, Clark H. Pinnock, William Crockett, Four Views of Hell (Zondervan 2010) ; Denny Burk, John G. Stackhouse, Jr., Robin Parry, Jerry Walls, Preston Sprinkle, Stanley N. Gundry, Four Views of Hell (Zondervan 2016)

- ↑ The Table Talk Or Familiar Discourse of Martin Luther , 1848, page 226

- ↑ Smalcald Articles, Part II, Article II: Of the Mass.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Raynor, Shane (14 October 2015). "Should Christians pray for the dead?". Ministry Matters. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ↑ "Apology XXIV, 96". Archived from the original on 2015-10-26. Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- ↑ Martti Parvio: Mikael Agricolan käsitys kiirastulesta ja votiivimessuista. –Pentti Laasonen (ed.) Investigatio memoriae patrum. Libellus in honorem Kauko Pirinen. SKHST 93. Rauma 1975.

- ↑ "The Augsburg Confession". Archived from the original on 2019-06-02. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ↑

- ↑ Colin Buchanan, Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism (Scarecrow, 2006), 510.

- ↑ "Join us in Daily Prayer".

- ↑ Colin Buchanan, Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism (Scarecrow, 2006), s.v. "Petitions for the Departed", 356–357.

- ↑ REMARKS ON CERTAIN PASSAGES IN THE THIRTY-NINE ARTICLES. .

- ↑ Newman was working on An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine since 1842 (Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 517–520., and sent it to the printer in September 1845 (Ian Turnbull Kern, Newman the Theologian - University of Notre Dame Press 1990 ISBN 9780268014698, p. 149). He was received into the Catholic Church on 9 October of the same year.

- ↑ John Henry Newman, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, chapter 2, section 3, paragraph 2.

- ↑ Don S. Armentrout and Robert Boak Slocum, eds, An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church (Church Publishing, 2000), 427.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Leonel L. Mitchell, Praying Shapes Believing: A Theological Commentary on The Book of Common Prayer (Church Publishing, 1991), 224.

- ↑ C. S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (Mariner Books, 2002), 108–109.

- ↑ "The Twenty-Five Articles of Religion (Methodist)". CRI / Voice, Institute. Archived from the original on 2017-12-18. Retrieved 2009-04-11.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Jerry L. Walls, Purgatory: The Logic of Total Transformation (Oxford University Press 2012), p. 174 ; cf. Jerry L. Walls, Heaven: The Logic of Eternal Joy (Oxford University Press 2002), pp. 53−62 and Jerry L. Walls, "Purgatory for Everyone"

- ↑ "Jerry Walls, PhD". HBU.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-05-03..

- ↑ Jerry L. Walls, Purgatory: The Logic of Total Transformation (Oxford University Press 2012), pp. 11–13

- ↑ Walls, 2012, pp. 14–17

- ↑ Walls, 2012, pp. 17−22

- ↑ Walls, 2012, pp. 22–24

- ↑ For example, Walls, 2012, p. 71

- ↑ Walls, 2012, pp. 76, 90.

- ↑ Walls 2012, p. 90

- ↑ "What Do Mormons Believe (The God Makers)?". www.christiandataresources.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- ↑ "Spirit Prison – The Encyclopedia of Mormonism". eom.byu.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-04-02. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- ↑ "There are three categories of men; the wholly pious and the arch-sinners are not purified, but only those between these two classes" (Jewish Encyclopedia: Gehenna )

- ↑ Maimonides’ Introduction to Perek Helek, ed. and transl. by Maimonides Heritage Center, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Maimonides’ Introduction to Perek Helek, ed. and transl. by Maimonides Heritage Center, pp. 22–23.

- ↑

- ↑ Das Johannesbuch der Mandäer, ed. and transl. by Mark Lidzbarski, part 2, Gießen 1915, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Hans Jonas: The Gnostic Religion, 3. ed., Boston 2001, p. 117.

- ↑ Günther, Sebastian, Todd Lawson, and Christian Mauder. "Roads to Paradise." Eschatology and Concepts of the Hereafter in Islam 1 (2017): 2.

- ↑ Hamza, Feras. "Temporary Hellfire Punishment and the Making of Sunni Orthodoxy." Roads to Paradise: Eschatology and Concepts of the Hereafter in Islam (2 vols.). Brill, 2017. 371-406.

- ↑

- ↑ 143.0 143.1

- ↑ Eileen Gardiner (10 February 2006). "About Zoroastrian Hell". Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

Further reading[edit]

- Hanna, Edward Joseph (1911). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Vanhoutte, Kristof K.P. and McCraw, Benjamin W. (eds.). Purgatory. Philosophical Dimensions (Palgrave MacMillan, 2017)

- Gould, James B. Understanding Prayer for the Dead: Its Foundation in History and Logic (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2016).

- Le Goff, Jacques. The Birth of Purgatory (U of Chicago Press, 1986).

- Pasulka, Diana Walsh. Heaven Can Wait: Purgatory in Catholic Devotional and Popular Culture (Oxford UP, 2015) online review

- Tingle, Elizabeth C. Purgatory and Piety in Brittany 1480–1720 (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013).

- Purgatory at the Internet Archive by F. X. Schouppe (1893) London: Burns & Oates.

External links[edit]

- Is Purgatory in the Bible? on Internet Archive

- Church Fathers on Purgatory

- Purgatory. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2009.

- English c. 1200 wall painting with an image of a ladder, reminiscent of icons such as the Ladder of Divine Ascent, which has been interpreted as a "purgatorial ladder"

- Quran Inspector: Chapter 7: "The Purgatory (Al-A'araf)" ( سورة الأعراف ) at submission.org