Malaysia Airlines Flight 370

The missing aircraft pictured in December 2011 | |

| Disappearance | |

|---|---|

| Date | 8 March 2014 |

| Summary | Inconclusive, some debris found |

| Site | Indian Ocean, most likely southern |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 777-200ER |

| Operator | Malaysia Airlines |

| IATA flight No. | MH370 |

| ICAO flight No. | MAS370 |

| Call sign | Malaysian 370 |

| Registration | 9M-MRO |

| Flight origin | Kuala Lumpur International Airport |

| Destination | Beijing Capital International Airport |

| Occupants | 239 |

| Passengers | 227 |

| Crew | 12 |

| Fatalities | 239 (presumed) |

| Survivors | 0 (presumed) |

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 (MH370/MAS370)[lower-alpha 1] was an international passenger flight operated by Malaysia Airlines that disappeared from radar on 8 March 2014, while flying from Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Malaysia to its planned destination, Beijing Capital International Airport in China.[1] It has not been determined what caused its disappearance.

The crew of the Boeing 777-200ER, with registration mark 9M-MRO, last communicated with air traffic control (ATC) around 38 minutes after takeoff when the flight was over the South China Sea. The aircraft was lost from ATC's secondary surveillance radar screens minutes later, but was tracked by the Malaysian military's primary radar system for another hour, deviating westward from its planned flight path, crossing the Malay Peninsula and Andaman Sea. It left radar range 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) northwest of Penang Island in northwestern Peninsular Malaysia.

With all 227 passengers and 12 crew aboard presumed dead, the disappearance of Flight 370 was the deadliest incident involving a Boeing 777, the deadliest of 2014, and the deadliest in Malaysia Airlines' history until it was surpassed in all three regards by Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which was shot down while flying over Ukraine four months later on 17 July 2014.

The search for the missing airplane became the most expensive search in the history of aviation. It focused initially on the South China Sea and Andaman Sea, before a novel analysis of the aircraft's automated communications with an Inmarsat satellite indicated that the plane had traveled far southward over the southern Indian Ocean. The lack of official information in the days immediately after the disappearance prompted fierce criticism from the Chinese public, particularly from relatives of the passengers, as most people on board Flight 370 were of Chinese origin. Several pieces of debris washed ashore in the western Indian Ocean during 2015 and 2016; many of these were confirmed to have originated from Flight 370.

After a three-year search across 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) of ocean failed to locate the aircraft, the Joint Agency Coordination Centre heading the operation suspended its activities in January 2017. A second search launched in January 2018 by private contractor Ocean Infinity also ended without success after six months.

Relying mostly on analysis of data from the Inmarsat satellite with which the aircraft last communicated, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) proposed initially that a hypoxia event was the most likely cause given the available evidence, although no consensus has been reached concerning this theory among investigators. At various stages of the investigation, possible hijacking scenarios were considered, including crew involvement, and suspicion of the airplane's cargo manifest; many disappearance theories regarding the flight have also been reported by the media.

The Malaysian Ministry of Transport's final report from July 2018 was inconclusive. It highlighted Malaysian ATC's failures to attempt to communicate with the aircraft shortly after its disappearance. In the absence of a definitive cause of disappearance, air transport industry safety recommendations and regulations citing Flight 370 have been implemented to prevent a repetition of the circumstances associated with the loss. These include increased battery life on underwater locator beacons, lengthening of recording times on flight data recorders and cockpit voice recorders, and new standards for aircraft position reporting over open ocean.

Timeline[edit]

The aircraft, a Boeing 777-200ER operated by Malaysia Airlines, last made voice contact with ATC at 01:19 MYT, 8 March (17:19 UTC, 7 March) when it was over the South China Sea, less than an hour after takeoff. It disappeared from ATC radar screens at 01:22 MYT, but was still tracked on military radar as it turned sharply away from its original northeastern course to head west and cross the Malay Peninsula, continuing that course until leaving the range of the military radar at 02:22 while over the Andaman Sea, 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) northwest of Penang Island in northwestern Malaysia.

The multinational search effort for the aircraft, which was to become the most expensive aviation search in history,[2][3][4] began in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea,[5] where the aircraft's signal was last detected on secondary surveillance radar, and was soon extended to the Strait of Malacca and Andaman Sea. Analysis of satellite communications between the aircraft and Inmarsat's satellite communications network concluded that the flight continued until at least 08:19 and flew south into the southern Indian Ocean, although the precise location cannot be determined. Australia assumed charge of the search on 17 March, when the search effort began to emphasise the southern Indian Ocean. On 24 March, the Malaysian government noted that the final location determined by the satellite communication was far from any possible landing sites, and concluded, "Flight MH370 ended in the southern Indian Ocean."[6]

From October 2014 to January 2017, a comprehensive survey of 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) of sea floor about 1,800 km (1,100 mi; 970 nmi) southwest of Perth, Western Australia, yielded no evidence of the aircraft. Several pieces of marine debris found on the coast of Africa and on Indian Ocean islands off the coast of Africa—the first of which was discovered on 29 July 2015 on Réunion—have been confirmed as pieces of Flight 370.[7][8][9][10] The bulk of the aircraft has not been located, prompting many theories about its disappearance.

On 22 January 2018, a search by private US marine exploration company Ocean Infinity began in the search zone around , the most likely crash site according to the drift study published in 2017.[11][12][13] In a previous search attempt, Malaysia had established a Joint Investigation Team (JIT) to investigate the incident, working with foreign aviation authorities and experts. Malaysia released a final report concerning Flight 370 in October 2017.[14] Neither the crew nor the aircraft's communication systems relayed a distress signal, indications of bad weather, or technical problems before the aircraft vanished. Two passengers travelling on stolen passports were investigated, but eliminated as suspects. Malaysian police identified the captain as the prime suspect if human intervention was the cause of the disappearance, after clearing all others on the flight of suspicion over possible motives. Power was lost to the aircraft's satellite data unit (SDU) at some point between 01:07 and 02:03; the SDU logged onto Inmarsat's satellite communication network at 02:25, which was three minutes after the aircraft had left the range of radar. Based on analysis of the satellite communications, the aircraft was postulated to have turned south after passing north of Sumatra and then to have flown for six hours with little deviation in its track, ending when its fuel was exhausted.[15]

With the loss of all 239 lives aboard, Flight 370 is the second-deadliest incident involving a Boeing 777 and the second-deadliest incident of Malaysia Airlines' history, second to Flight 17 in both categories. Malaysia Airlines was struggling financially, a problem that was exacerbated by a decrease of ticket sales after the disappearance of Flight 370 and the downing of Flight 17; the airline was renationalised by the end of 2014. The Malaysian government received significant criticism, especially from China, for failing to disclose information promptly during the early weeks of the search. Flight 370's disappearance brought to public attention the limits of aircraft tracking and flight recorders, including the limited battery life of underwater locator beacons (an issue that had been raised about four years earlier following the loss of Air France Flight 447, but had never been resolved). In response to Flight 370's disappearance, the International Civil Aviation Organization adopted new standards for aircraft position reporting over open ocean, extended recording time for cockpit voice recorders, and, starting from 2020, new aircraft designs have been required to have a means of recovering the flight recorders, or the information they contain, before they sink into the water.[16]

Aircraft[edit]

Flight 370 was operated with a Boeing 777-2H6ER,[lower-alpha 2] serial number 28420, registration 9M-MRO. It was the 404th Boeing 777 produced,[18] first flown on 14 May 2002, and was delivered new to Malaysia Airlines on 31 May 2002. The aircraft was powered by two Rolls-Royce Trent 892 engines[18] and configured to carry 282 passengers in total capacity.[19] It had accumulated 53,471.6 hours and 7,526 cycles (takeoffs and landings) in service[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". and had not previously been involved in any major incidents,[21] though a minor incident while taxiing at Shanghai Pudong International Airport in August 2012 resulted in a broken wing tip.[22][23] Its last maintenance "A check" was carried out on 23 February 2014.[24] The aircraft was in compliance with all applicable Airworthiness Directives for the airframe and engines. A replenishment of the crew member oxygen system was performed on 7 March 2014, a routine maintenance task; an examination of this procedure found nothing unusual.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". Ten years after MH370's disappearance, however, leaked documents have shown that MH370 was given supplemental fuel and crew member oxygen supplies just before takeoff.[25]

The Boeing 777 was introduced in 1994 and has an excellent safety record.[26][27] Since its first commercial flight in June 1995, the type has suffered only seven other hull losses: the crash of British Airways Flight 38 in 2008; a cockpit fire in a parked EgyptAir Flight 667 at Cairo International Airport in 2011;[28][29] the crash of Asiana Airlines Flight 214 in 2013, in which three people died; Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which was shot down over Ukraine, killing all 298 people aboard in July 2014;[30][31] Emirates Flight 521, which crashed and burned out while landing at Dubai International Airport in August 2016;[32] and in November 2017, the seventh Boeing 777 hull loss occurred when a Singapore Airlines 777-200ER was written off after catching fire and burning out at Singapore Changi Airport.[33]

Passengers and crew[edit]

| Nation[34] | Count |

|---|---|

| Australia | 6 |

| Canada | 2 |

| China | 153[lower-alpha 3] |

| France | 4 |

| India[36] | 5 |

| Indonesia | 7 |

| Iran | 2[lower-alpha 4] |

| Malaysia | 50[lower-alpha 5] |

| Netherlands | 1 |

| New Zealand | 2 |

| Russia | 1 |

| Taiwan | 1 |

| Ukraine | 2 |

| United States | 3 |

| Total (14 Nationalities) | 239 |

The aircraft was carrying 12 Malaysian crew members and 227 passengers from 14 different nations.[38] On the day of the disappearance, Malaysia Airlines released the names and nationalities of the passengers and crew, based on the flight manifest.[34] The passenger list was later modified to include two Iranian passengers travelling on stolen Austrian and Italian passports.[37]

Crew[edit]

All 12 crew members—two pilots and 10 cabin crew—were Malaysian citizens.[34]

- The pilot in command was 53-year-old Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah from Penang. He joined Malaysia Airlines as a cadet pilot in 1981, and after training and receiving his commercial pilot's licence, he became a second officer with the airline in 1983. He was promoted to captain of Boeing 737-400 airliners in 1991, captain of Airbus A330-300 in 1996, and captain of Boeing 777-200 in 1998. He had been a type-rating instructor and a type-rating examiner since 2007. Zaharie had a total of 18,365 hours of flying experience.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [39][40]

- The co-pilot was 27-year-old First Officer Fariq Abdul Hamid. He joined Malaysia Airlines as a cadet pilot in 2007; after becoming a second officer of Boeing 737-400 airliners, he was promoted to first officer of the Boeing 737-400 in 2010 and then transitioned to the Airbus A330-300 in 2012. In November 2013, he began training as first officer of Boeing 777-200 aircraft. Flight 370 was his final training flight, and he was scheduled to be examined on his next flight. Fariq had accumulated 2,763 hours of flying experience.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [41][42]

Passengers[edit]

Of the 227 passengers, 153 were Chinese citizens,[38] including a group of 19 artists with six family members and four staff returning from a calligraphy exhibition of their work in Kuala Lumpur; 38 passengers were Malaysian. The remaining passengers were from 12 different countries.[34][43] Twenty passengers, 12 of whom were from Malaysia and eight from China, were employees of Freescale Semiconductor.[43][44][45]

Through a 2007 agreement with Malaysia Airlines, Tzu Chi (an international Buddhist organisation) immediately sent specially trained teams to Beijing and Malaysia to give emotional assistance to passengers' families.[46][47] The airline also sent its own team of caregivers and volunteers[48] and agreed to bear the expense of bringing family members of the passengers to Kuala Lumpur and providing them with accommodation, medical care, and counselling.[49] Altogether, 115 family members of the Chinese passengers flew to Kuala Lumpur.[50] Some other family members chose to remain in China, fearing they would feel too isolated in Malaysia.[51]

Flight and disappearance[edit]

Flight 370 was a scheduled flight in the early morning of Saturday, 8 March 2014, from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to Beijing, China. It was one of two daily flights operated by Malaysia Airlines from its hub at Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) to Beijing Capital International Airport—scheduled to depart at 00:35 local time (MYT; UTC+08:00) and arrive at 06:30 local time (CST; UTC+08:00).[52][53] On board were two pilots, 10 cabin crew, 227 passengers, and 14,296 kg (31,517 lb) of cargo.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

The planned flight duration was 5 hours and 34 minutes, which would consume an estimated 37,200 kg (82,000 lb) of jet fuel. The aircraft carried 49,100 kilograms (108,200 lb) of fuel, including reserves, allowing an endurance of 7 hours and 31 minutes. The extra fuel was enough to divert to alternate airports—Jinan Yaoqiang International Airport and Hangzhou Xiaoshan International Airport—which would require 4,800 kg (10,600 lb) or 10,700 kg (23,600 lb), respectively, to reach from Beijing.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

Departure[edit]

At 00:42 MYT, Flight 370 took off from runway 32R,[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". and was cleared by air traffic control (ATC) to climb to flight level 180[lower-alpha 6]—approximately 18,000 feet (5,500 m)—on a direct path to navigational waypoint IGARI (located at ). Voice analysis has determined that the first officer communicated with ATC while the flight was on the ground and that the Captain communicated with ATC after departure.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". Shortly after departure, the flight was transferred from the airport's ATC to "Lumpur Radar" air traffic control on frequency 132.6 MHz. ATC over peninsular Malaysia and adjacent waters is provided by the Kuala Lumpur Area Control Centre (ACC); Lumpur Radar is the name of the frequency used for en route air traffic.[54] At 00:46, Lumpur Radar cleared Flight 370 to flight level 350[lower-alpha 6]—approximately 35,000 ft (10,700 m). At 01:01, Flight 370's crew reported to Lumpur Radar that they had reached flight level 350, which they confirmed again at 01:08.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [55]

Communication lost[edit]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The aircraft's final transmission was an automated position report, sent using the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) protocol at 01:06 MYT.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [57][58]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". Among the data provided in this message was the total fuel remaining: 43,800 kg (96,600 lb).[59]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". The last verbal signal to air traffic control occurred at 01:19:30, when Captain Zaharie acknowledged a transition from Lumpur Radar to Ho Chi Minh ACC:[lower-alpha 7][20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [55][60]

Lumpur Radar: "Malaysian three seven zero, contact Ho Chi Minh one two zero decimal nine. Good night."

Flight 370: "Good night. Malaysian three seven zero."

The crew was expected to signal ATC in Ho Chi Minh City as the aircraft passed into Vietnamese airspace, just north of the point where contact was lost.[61][62] The captain of another aircraft attempted to contact the crew of Flight 370 shortly after 01:30, using the international air distress frequency, to relay Vietnamese air traffic control's request for the crew to contact them; the captain said he was able to establish communication, but heard only "mumbling" and static.[63] Calls made to Flight 370's cockpit at 02:39 and 07:13 were unanswered, but acknowledged by the aircraft's satellite data unit.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [58]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

Radar[edit]

At 01:20:31 MYT, Flight 370 was observed on radar at the Kuala Lumpur ACC as it passed the navigational waypoint IGARI () in the Gulf of Thailand; five seconds later, the Mode-S symbol disappeared from radar screens.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". At 01:21:13, Flight 370 disappeared from the radar screen at Kuala Lumpur ACC and was lost at about the same time on radar at Ho Chi Minh ACC, which reported that the aircraft was at the nearby waypoint BITOD.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [55] Air traffic control uses secondary radar, which relies on a signal emitted by a transponder on each aircraft; therefore, the ADS-B transponder was no longer functioning on Flight 370 after 01:21. The final transponder data indicated that the aircraft was flying at its assigned cruise altitude of flight level 350[lower-alpha 6] and was travelling at 471 knots (872 km/h; 542 mph) true airspeed.[64] There were few clouds around this point, and no rain or lightning nearby.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". Later analysis estimated that Flight 370 had 41,500 kg (91,500 lb) of fuel when it disappeared from secondary radar.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

At the time that the transponder stopped functioning, the Malaysian military's primary radar showed Flight 370 turning right, but then beginning a left turn to a southwesterly direction.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". From 01:30:35 until 01:35, military radar showed Flight 370 at 35,700 ft (10,900 m)[lower-alpha 8] on a 231° magnetic heading, with a ground speed of 496 knots (919 km/h; 571 mph). Flight 370 continued across the Malay Peninsula, fluctuating between 31,000 and 33,000 ft (9,400 and 10,100 m) in altitude.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". A civilian primary radar at Sultan Ismail Petra Airport with a 60 nmi (110 km; 69 mi) range made four detections of an unidentified aircraft between 01:30:37 and 01:52:35; the tracks of the unidentified aircraft are "consistent with those of the military data".[lower-alpha 9][20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". At 01:52, Flight 370 was detected passing just south of the island of Penang. From there, the aircraft flew across the Strait of Malacca, passing close to the waypoint VAMPI, and Pulau Perak at 02:03, after which it flew along air route N571 to waypoints MEKAR, NILAM, and possibly IGOGU.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". The last known radar detection, from a point near the limits of Malaysian military radar, was at 02:22, 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) after passing waypoint MEKAR[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". (which is 237 nmi (439 km; 273 mi) from Penang) and 247.3 nmi (458.0 km; 284.6 mi) northwest of Penang airport at an altitude of 29,500 ft (9,000 m).[65][66]

Countries were reluctant to release information collected from military radar because of sensitivity about revealing their capabilities. Indonesia has an early-warning radar system, but its ATC radar did not register any aircraft with the transponder code used by Flight 370, despite the aircraft possibly having flown near, or over, the northern tip of Sumatra.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [55] Indonesian military radar tracked Flight 370 earlier when en route to waypoint IGARI before the transponder is thought to have been turned off, but did not provide information on whether it was detected afterwards.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [67] Thailand and Vietnam also detected Flight 370 on radar before the transponder stopped working. The radar position symbols for the transponder code used by Flight 370 vanished after the transponder is thought to have been turned off.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". Vietnam's deputy minister of transport Pham Quy Tieu stated that Vietnam had noticed MH370 turning back toward the west and that its operators had twice informed Malaysian authorities the same day on 8 March.[68] Thai military radar detected an aircraft that might have been Flight 370, but it is not known at what time the last radar contact was made, and the signal did not include identifying data.[69] Also, the flight was not detected by Australia's conventional system[70] or its long-range JORN over-the-horizon radar system, which has an official range of 3,000 km (1,900 mi); the latter was not in operation on the night of the disappearance.[71]

Satellite communication resumes[edit]

At 02:25 MYT, the aircraft's satellite communication system sent a "log-on request" message—the first message since the ACARS transmission at 01:07—which was relayed by satellite to a ground station, both operated by satellite telecommunications company Inmarsat. After logging on to the network, the satellite data unit aboard the aircraft responded to hourly status requests from Inmarsat and two ground-to-aircraft telephone calls, at 02:39 and 07:13, both unanswered by the cockpit.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [58] The final status request and aircraft acknowledgement occurred at 08:10, about 1 hour and 40 minutes after the flight was scheduled to arrive in Beijing. The aircraft sent a log-on request at 08:19:29, which was followed, after a response from the ground station, by a "log-on acknowledgement" message at 08:19:37. The log-on acknowledgement is the last piece of data received from Flight 370. The aircraft did not respond to a status request from Inmarsat at 09:15.[56][58][72][73]

Response by air traffic control[edit]

At 01:38 MYT, Ho Chi Minh Area Control Centre (ACC) contacted Kuala Lumpur Area Control Centre to query the whereabouts of Flight 370 and informed Kuala Lumpur that ACC had not established verbal communication with Flight 370, which was last detected by radar at waypoint BITOD. The two centres exchanged four more calls during the next 20 minutes with no new information.[55][74]

At 02:03, Kuala Lumpur ACC relayed to Ho Chi Minh ACC information received from Malaysia Airlines' operations centre that Flight 370 was in Cambodian airspace. Ho Chi Minh ACC contacted Kuala Lumpur ACC twice in the following eight minutes asking for confirmation that Flight 370 was in Cambodian airspace.[55] At 02:15, the watch supervisor at Kuala Lumpur ACC queried Malaysia Airlines' operations centre, which said that it could exchange signals with Flight 370 and that Flight 370 was in Cambodian airspace.[74] Kuala Lumpur ACC contacted Ho Chi Minh ACC to ask whether the planned flight path for Flight 370 passed through Cambodian airspace. Ho Chi Minh ACC responded that Flight 370 was not supposed to enter Cambodian airspace and that they had already contacted Phnom Penh ACC (which controls Cambodian airspace), which had no communication with Flight 370.[55] Kuala Lumpur ACC contacted Malaysia Airlines' operations centre at 02:34, inquiring about the communication status with Flight 370, and were informed that Flight 370 was in a normal condition based on a signal download and that it was located at .[74] Later, another Malaysia Airlines aircraft (Flight 386 bound for Shanghai) attempted, at the request of Ho Chi Minh ACC, to contact Flight 370 on the Lumpur Radar frequency – the frequency on which Flight 370 last made contact with Malaysian air traffic control – and on emergency frequencies. The attempt was unsuccessful.[55][75]

At 03:30, Malaysia Airlines' operations centre informed Kuala Lumpur ACC that the locations it had provided earlier were "based on flight projection and not reliable for aircraft positioning." Over the next hour, Kuala Lumpur ACC contacted Ho Chi Minh ACC asking whether they had signaled Chinese air traffic control. At 05:09, Singapore ACC was queried for information about Flight 370. At 05:20, an undisclosed official contacted Kuala Lumpur ACC requesting information about Flight 370; he opined that, based on known information, "MH370 never left Malaysian airspace."[55]

The watch supervisor at Kuala Lumpur ACC activated the Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre (ARCC) at 05:30, more than four hours after communication was lost with Flight 370.[74] The ARCC is a command post at an Area Control Centre that coordinates search-and-rescue activities when an aircraft is lost.

===

Presumed loss ===

Malaysia Airlines issued a media statement at 07:24 MYT, one hour after the scheduled arrival time of the flight at Beijing, stating that communication with the flight had been lost by Malaysian ATC at 02:40 and that the government had initiated search-and-rescue operations;[76] the time when contact was lost was later corrected to 01:21.[76] Neither the crew nor the aircraft's communication systems relayed a distress signal, indications of bad weather, or technical problems before the aircraft vanished from radar screens.[77]

On 24 March, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak appeared before media at 22:00 local time to give a statement regarding Flight 370, during which he announced that he had been briefed by the Air Accidents Investigation Branch that it and Inmarsat (the satellite data provider) had concluded that the airliner's last position before it disappeared was in the southern Indian Ocean. As no places exist where it could have landed, the aircraft must therefore have crashed into the sea.[78]

Just before Najib spoke at 22:00 MYT, an emergency meeting was called in Beijing for relatives of Flight 370 passengers.[78] Malaysia Airlines announced that Flight 370 was assumed lost with no survivors. It notified most of the families in person or via telephone, and some received an SMS (in English and Chinese) informing them that the aircraft likely had crashed with no survivors.[6][78][79][80]

On 29 January 2015, the director general of the Department of Civil Aviation Malaysia, Azharuddin Abdul Rahman, announced that the status of Flight 370 would be changed to an "accident", in accordance with the Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation, and that all passengers and crew are presumed to have lost their lives.[81]

If the official assumption is confirmed, Flight 370 was, at the time of its disappearance, the deadliest aviation incident in the history of Malaysian Airlines, surpassing the 1977 hijacking and crash of Malaysian Airline System Flight 653 that killed all 100 passengers and crew aboard, and the deadliest involving a Boeing 777, surpassing Asiana Airlines Flight 214 (three fatalities).[82][83] In both of those categories, Flight 370 was surpassed 131 days later by Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, another Boeing 777-200ER, which was shot down on 17 July 2014, killing all 298 people aboard.[30]

Reported sightings[edit]

The news media reported several sightings of an aircraft fitting the description of the missing Boeing 777. For example, on 19 March 2014, CNN reported that witnesses including fishermen, an oil rig worker, and people on the Kuda Huvadhoo atoll in the Maldives saw the missing airliner. A fisherman claimed to have seen an unusually low-flying aircraft off the coast of Kota Bharu, while an oil-rig worker 186 miles (299 km) southeast of Vung Tau claimed he saw a "burning object" in the sky that morning, a claim credible enough for the Vietnamese authorities to send a search-and-rescue mission, and Indonesian fishermen reported witnessing an aircraft crash near the Malacca Straits.[84] Three months later, The Daily Telegraph reported that a British woman sailing in the Indian Ocean claimed to have seen an aircraft on fire.[85]

Search[edit]

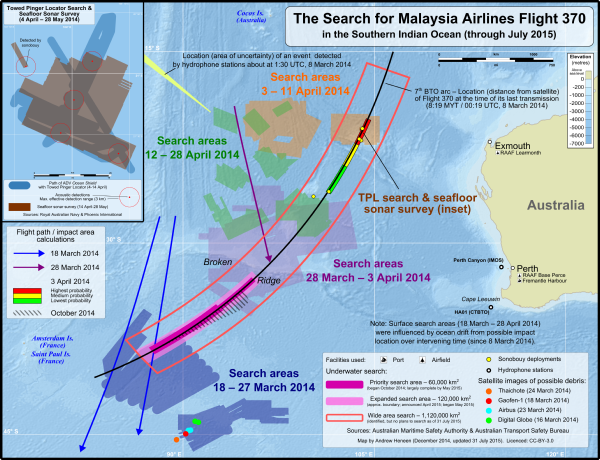

A search-and-rescue effort was launched in southeast Asia soon after the disappearance of Flight 370. Following the initial analysis of communications between the aircraft and a satellite, the surface search was moved to the southern Indian Ocean one week after the aircraft's disappearance. Between 18 March and 28 April, 19 vessels and 345 sorties by military aircraft searched over 4,600,000 km2 (1,800,000 sq mi).[86] The final phase of the search was a bathymetric survey and sonar search of the sea floor, about 1,800 kilometres (970 nmi; 1,100 mi) southwest of Perth, Western Australia.[87] With effect from 30 March 2014, the search was coordinated by the Joint Agency Coordination Centre (JACC), an Australian government agency that was established specifically to manage the effort to locate and recover Flight 370, and which primarily involved the Malaysian, Chinese, and Australian governments.[88]

On 17 January 2017, the official search for Flight 370—which had proven to be the most expensive search operation in aviation history[89][90]—was suspended after yielding no evidence of the aircraft other than some marine debris on the coast of Africa.[91][92][93][94] The final ATSB report, published on 3 October 2017, stated that the underwater search for the aircraft, as of 30 June 2017[update], had cost a total of US$155 million (~$ in 2023). The underwater search accounted for 86% of this amount, bathymetry 10%, and programme management 4%. Malaysia had supported 58% of the total cost, Australia 32%, and China 10%.[95] The report also concluded that the location where the aircraft went down had been narrowed to an area of 25,000 km2 (9,700 sq mi) by using satellite images and debris drift analysis.[96][97]

In January 2018, the private American marine-exploration company Ocean Infinity resumed the search for MH370 in the narrowed 25,000 km2 area, using the Norwegian ship Seabed Constructor.[98][99][100][101] The search area was significantly extended during the course of the search, and by the end of May 2018, the vessel had searched a total area of more than 112,000 km2 (43,000 sq mi) using eight autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs).[102][103] The contract with the Malaysian government ended soon afterward, and the search was concluded without success on 9 June 2018.[104]

Southeast Asia[edit]

The Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre (ARCC) was activated at 05:30 MYT—four hours after communication was lost with the aircraft—to coordinate search and rescue efforts.[74] Search efforts began in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea. On the second day of the search, Malaysian officials said that radar recordings indicated that Flight 370 may have turned around before vanishing from radar screens;[43] the search zone was expanded to include part of the Strait of Malacca.[105] On 12 March, the chief of the Royal Malaysian Air Force announced that an unidentified aircraft—believed to be Flight 370—had travelled across the Malay peninsula and was last sighted on military radar 370 km (200 nmi; 230 mi) northwest of the island of Penang; search efforts were subsequently increased in the Andaman Sea and Bay of Bengal.[66]

Records of signals sent between the aircraft and a communications satellite over the Indian Ocean revealed that the plane had continued flying for almost six hours after its final sighting on Malaysian military radar. Initial analysis of these communications determined that Flight 370 was along one of two arcs—equidistant from the satellite—when its last signal was sent. On 15 March, the same day upon which the analysis was disclosed publicly, authorities announced that they would abandon search efforts in the South China Sea, Gulf of Thailand, and Strait of Malacca in order to focus their efforts on the two corridors. The northern arc—from northern Thailand to Kazakhstan—was soon discounted, for the aircraft would have had to pass through heavily militarised airspace, and those countries claimed that their military radar would have detected an unidentified aircraft entering their airspace.[106][107][108]

Southern Indian Ocean[edit]

The emphasis of the search was shifted to the southern Indian Ocean west of Australia and within Australia's aeronautical and maritime Search and Rescue regions that extend to 75°E longitude.[109][110] Accordingly, on 17 March, Australia agreed to manage the search in the southern locus from Sumatra to the southern Indian Ocean.[111][112]

Initial search[edit]

From 18 to 27 March 2014, the search effort focused on a 315,000 km2 (122,000 sq mi) area about 2,600 km (1,400 nmi; 1,600 mi) southwest of Perth.[113] The search area, which Australian prime minister Tony Abbott called "as close to nowhere as it's possible to be", is renowned for its strong winds, inhospitable climate, hostile seas, and deep ocean floors.[114][115] Satellite imagery of the region was analysed;[116] several objects of interest and two possible debris fields were identified on images made between 16 and 26 March. None of these possible objects were found by aircraft or ships.[117]

Revised estimates of the radar track and the aircraft's remaining fuel led to a move of the search 1,100 km (590 nmi; 680 mi) northeast of the previous area on 28 March,[118][119][120] which was followed by another shift on 4 April.[121][122] Between 2 and 17 April, an effort was made to detect the underwater locator beacons (ULBs, informally known as "pingers") attached to the aircraft's flight recorders, because the beacons' batteries were expected to expire around 7 April.[123][124] Australian naval cutter ADV Ocean Shield, equipped with a towed pinger locator (TPL), joined China's Haixun 01, equipped with a hand-held hydrophone, and the Royal Navy's HMS Echo, equipped with a hull-mounted hydrophone, in the search.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [97]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [123][125][126] Operators considered the effort to have little chance of success[127] given the vast search area and the fact that a TPL can only search up to 130 km2 (50 sq mi) per day.[127]

Between 4 and 8 April, several acoustic detections were made that were close to the frequency and rhythm of the sound emitted by the flight recorders' ULBs; analysis of the acoustic detections determined that, although unlikely, the detections could have come from a damaged ULB.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". A sonar search of the seafloor near the detections was carried out between 14 April and 28 May but yielded no sign of Flight 370.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". In a March 2015 report, it was revealed that the battery of the ULB attached to Flight 370's flight data recorder may have expired in December 2012 and thus may not have been as capable of sending signals as would an unexpired battery.[128][129]

Underwater search[edit]

In late June 2014, details of the next phase of the search were announced;[130] officials have called this phase the "underwater search" despite the previous seafloor sonar survey.[131] Continued refinement of the analysis of Flight 370's satellite communications identified a "wide area search" along the "7th arc"[lower-alpha 10] where Flight 370 was located when it last communicated with the satellite. The priority search area was in the southern extent of the wide area search.[132] Some of the equipment used for the underwater search is most effective when towed 200 m (650 ft) above the seafloor at the end of a 9.7 km (6 mi) cable.[133] Available bathymetric data for this region was of poor resolution, thus necessitating a bathymetric survey of the search area before the underwater phase began.[134] Commencing in May, the survey charted around 208,000 km2 (80,000 sq mi) of seafloor until 17 December 2014, when it was suspended so that the ship conducting the survey could be mobilised in the underwater search.[135]

The governments of Malaysia, China, and Australia made a joint commitment to thoroughly search 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) of seafloor.[136] This phase of the search, which began on 6 October 2014,[132] used three vessels equipped with towed deep-water vehicles that use side-scan sonar, multi-beam echo sounders, and video cameras to locate and identify aircraft debris.[137] A fourth vessel participated in the search between January and May 2015, using an AUV to search areas that could not be effectively searched using equipment on the other vessels.[138][139][140] Following the discovery of the flaperon on Réunion, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) reviewed its drift calculations for debris from the aircraft and, according to the JACC, was satisfied that the search area was still the most likely crash site.[141] Reverse drift modelling of the debris, to determine its origin after 16 months, also supported the underwater search area, although this method is very imprecise over long periods.[141] On 17 January 2017, the three countries jointly announced the suspension of the search for Flight 370.[91][142]

2018 search[edit]

On 17 October 2017, Dutch-based Fugro and American company Ocean Infinity offered to resume the search for the aircraft.[143] In January 2018, Ocean Infinity announced that it was planning to resume the search in the narrowed 25,000 km2 (9,700 sq mi) area. The search attempt was approved by the Malaysian government, provided that payment would be made only if the wreckage were found.[98][99] Ocean Infinity chartered the Norwegian ship Seabed Constructor to perform the search.[101]

In late January, it was reported that the AIS tracking system had detected the vessel reaching the search zone on 21 January. The vessel then started moving to , the most likely crash site according to the drift study by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).[11] The planned search area of "site 1", where the search began, was 33,012 km2 (12,746 sq mi), while the extended search area covered a further 48,500 km2 (18,700 sq mi).[100] In April, a report by Ocean Infinity revealed that "site 4", farther northeast along the 7th arc,[lower-alpha 10] had been added to the search plan.[147] By the end of May 2018, the vessel had searched a total area of over 112,000 km2 (43,000 sq mi), using eight AUVs;[102][103] all areas of "site 1" (including areas beyond that originally planned for "site 1"), "site 2", and "site 3" had been searched.[148] The final phase of the search was conducted in "site 4" in May 2018,[148] "before the weather limits Ocean Infinity's ability to continue working this year."[149] Malaysia's new transport minister Loke Siew Fook announced on 23 May 2018 that the search for MH370 would conclude at the end of the month.[150] Ocean Infinity confirmed on 31 May that its contract with the Malaysian government had ended,[151][152] and it was reported on 9 June 2018 that the Ocean Infinity search had come to an end.[104] Ocean-floor mapping data collected during the search have been donated to the Nippon Foundation–GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project, to be incorporated into the global map of the ocean floor.[153][154]

In March 2019, in the wake of the fifth anniversary of the disappearance, the Malaysian government stated that it was willing to look at any "credible leads or specific proposals" regarding a new search.[155] Ocean Infinity stated that it was ready to resume the search on the same no-find, no-fee basis, believing that it would benefit from the experience that it had gained from its search for the wreck of Argentinian submarine ARA San Juan and bulk carrier ship Stellar Daisy. Ocean Infinity believed that the most probable location was still somewhere along the 7th arc around the area identified previously and upon which its 2018 search was based.[156]

Potential 2024 search[edit]

In March 2022, Ocean Infinity committed to resuming its search in 2023 or 2024, pending approval by the Malaysian government.[157] In 2023, Ocean Infinity was reviewing data from their previous 2018 search to ensure nothing was missed. CEO Oliver Plunkett hoped to resume the search in the summer of 2023 using Ocean Infinity's new Armada vessel. The transportation minister of Malaysia, Wee Ka Siong, requested credible new evidence from Ocean Infinity in order to resume the search, which Plunkett is allegedly in possession of.[158] Claims of yet-to-be-identified new evidence has incited victims' families to further push for another search.[159]

In March 2024, days before the tenth anniversary of the disappearance, Malaysia said it would consult with Australia about collaborating on another expedition by the Ocean Infinity team.[160][161][162]

Marine debris[edit]

By October 2017, 20 pieces of debris believed to be from 9M-MRO had been recovered from beaches in the western Indian Ocean;[163] 18 of the items were "identified as being very likely or almost certain to originate from MH370", while the other two were "assessed as probably from the accident aircraft."[97]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". On 16 August 2017, the ATSB released two reports: the analysis of satellite imagery collected on 23 March 2014, two weeks after MH370 disappeared, classifying 12 objects in the ocean as "probably man-made";[164] and a drift study of the recovered objects by the CSIRO, identifying the crash area "with unprecedented precision and certainty" at , northeast of the main 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) underwater search zone.[165][166]

Flaperon[edit]

The first item of debris to be positively identified as originating from Flight 370 was the right flaperon (a trailing edge control surface).[167][168][169] It was discovered in late July 2015 on a beach in Saint-André, Réunion, an island in the western Indian Ocean, about 4,000 km (2,200 nmi; 2,500 mi) west of the underwater search area.[170] The item was transported from Réunion (an overseas department of France) to Toulouse, where it was examined by France's civil aviation accident investigation agency, the Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (BEA), and a French defence ministry laboratory.[170] Malaysia sent its own investigators to both Réunion and Toulouse.[170][171] On 3 September 2015, French officials announced that serial numbers found on internal components of the flaperon linked it "with certainty" to Flight 370.[172] These serial numbers were retrieved using a borescope.[173][174][175][176]

After the discovery, French police conducted a search of the waters around Réunion for additional debris,[170][177][178] and found a damaged suitcase that was initially linked to Flight 370,[179] but officials have since doubted this connection.[180] The location of the discovery was consistent with models of debris dispersal 16 months after an origin in the search area then in progress off the west coast of Australia.[141][170][181][182] A Chinese water bottle and an Indonesian cleaning product were also found in the same area.[183][184]

In August 2015, France carried out an aerial search for possible marine debris around the island, covering an area of 120 by 40 km (75 by 25 mi) along the east coast of Réunion.[178] Foot patrols were also planned to search for debris along the beaches.[185] Malaysia asked authorities in neighbouring states to be on the alert for marine debris that might have come from an aircraft.[186] On 14 August, it was announced that no debris that could be traced to Flight 370 had been found at sea off Réunion, but that some items had been found on land.[187] Air and sea searches for debris ended on 17 August.[188]

The flaperon was covered in Lepas anatifera barnacles, which grow in certain patterns and only while underwater. Researchers have analyzed the barnacles on the flaperon in an attempt to deduce its path to Réunion.[189]

Parts from the right stabiliser and right wing[edit]

In late February 2016, an object bearing a stencilled label of "NO STEP" was found off the coast of Mozambique; early photographic analysis suggested that it could have come from the aircraft's horizontal stabiliser or from the leading edges of the wings.[7] The part was found by Blaine Gibson[190] on a sandbank in the Bazaruto Archipelago off the coast of Vilanculos[191] in southern Mozambique, around 2,000 km (1,200 mi) southwest of where the flaperon had been found the previous July.[192][193] The fragment was sent to Australia, where experts identified it as almost certainly a horizontal stabiliser panel from 9M-MRO.[194][195]

In December 2015, Liam Lotter had found a grey piece of debris on a beach in southern Mozambique, but only after reading in March 2016 about Gibson's find—some 300 km (190 mi) from his own—did his family alert authorities.[190] The piece was flown to Australia for analysis. It carried a stencilled code 676EB, which identified it as part of a Boeing 777 flap track fairing,[7][196] and the style of lettering matched that of stencils used by Malaysia Airlines, making it almost certain that the part came from 9M-MRO.[7][8][9][10][190][197]

The locations where the objects were found are consistent with the drift model performed by CSIRO,[8] further corroborating that the parts could have come from Flight 370.

Other debris[edit]

On 7 March 2016, more debris, possibly from the aircraft, was found on the island of Réunion. Ab Aziz Kaprawi, Malaysia's deputy transport minister, said that "an unidentified grey item with a blue border" might be linked to Flight 370. Both Malaysian and Australian authorities, coordinating the search in the South Indian Ocean, sent teams to verify whether the debris was from the missing aircraft.[198][199]

On 21 March 2016, South African archaeologist Neels Kruger found a grey piece of debris on a beach near Mossel Bay, South Africa, that had an unmistakable partial logo of Rolls-Royce, the manufacturer of the missing aircraft's engines.[200] The Malaysian ministry of transport acknowledged that the piece could be that of an engine cowling.[201] An additional piece of possible debris, suggested to have come from the interior of the aircraft, was found on the island of Rodrigues, Mauritius, in late March.[202] On 11 May 2016, Australian authorities determined that the two pieces of debris were "almost certainly" from Flight 370.[203]

Flap and further search[edit]

On 24 June 2016, Australian transport minister Darren Chester said that a piece of aircraft debris had been found on Pemba Island, off the coast of Tanzania.[204] It was handed over to the authorities so that experts from Malaysia could determine its origin.[205] On 20 July, the Australian government released photographs of the piece, which was believed to be an outboard flap from one of the aircraft's wings.[206] Malaysia's transport ministry confirmed on 15 September that the debris was indeed from the missing aircraft.[207]

On 21 November 2016, families of the victims announced that they would carry out a search for debris in December on the island of Madagascar.[208] On 30 November 2018, five pieces of debris recovered between December 2016 and August 2018 on the Malagasy coast, and believed by victims' relatives to be from MH370, were handed to Malaysian transport minister Anthony Loke.[209]

Texas A&M University mathematics professor Goong Chen has argued that the plane may have entered the sea vertically; any other angle of entry would make the aircraft splinter into many pieces, which would have been found already.[210][211]

Investigation[edit]

International participation[edit]

Malaysia quickly assembled a Joint Investigation Team (JIT), consisting of specialists from Malaysia, China, the United Kingdom, the United States, and France,[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [212] which was led in accordance with ICAO standards by "an independent investigator in charge".[213][214][215] The team consisted of an airworthiness group, an operations group, and a medical and human factors group. The airworthiness group were tasked with examining issues relating to maintenance records, structures, and systems of the aircraft; the operations group were to review the flight recorders, operations, and meteorology; and the medical and human factors group would investigate psychological, pathological, and survival factors.[216] Malaysia also announced, on 6 April 2014, that it had set up three ministerial committees: a Next of Kin Committee, a committee to organise the formation of the JIT, and a committee responsible for the Malaysian assets deployed in the search effort.[216] The criminal investigation was led by the Royal Malaysia Police,[81]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". assisted by Interpol and other relevant international law enforcement authorities.[217][218]

On 17 March, Australia took control of co-ordinating the search, rescue, and recovery operations. For the next six weeks, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) and ATSB worked to determine the search area, correlating information with the JIT and other government and academic sources, while the Joint Agency Coordination Centre (JACC) coordinated the search efforts. Following the fourth phase of the search, the ATSB took responsibility for defining the search area. In May, a search strategy working group was established by the ATSB to determine the most likely position of the aircraft at the 00:19 UTC (08:19 MYT) satellite transmission. The working group included aircraft and satellite experts from: Air Accidents Investigation Branch (UK), Boeing (US), Defence Science and Technology Group[lower-alpha 11] (Australia), Department of Civil Aviation (Malaysia), Inmarsat (UK), National Transportation Safety Board (US), and Thales (France).[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [220][221]

As of October 2018[update], France was the only country that was continuing the investigation (by means of its Air Transport Gendarmerie), with the intention of verifying all of the technical data transmitted, particularly those provided by Inmarsat.[222][223]

Interim and final reports[edit]

Two interim reports were issued in 8 March 2015, and March 2016. They contained factual information about the plane but no analysis. The final report from the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, published on 3 October 2017, was 440 pages and called for planes to be equipped with more precise flight tracking technology.[95] The final report from the Malaysian Ministry of Transport, was 1,500 pages, released on 30 July 2018.[224] It confirmed that the plane was manually turned around, taking it off its normal flight path just after 1am, "either by the pilot or a third party" and that the plane was missing for twenty minutes before anyone was alerted.[225][224] Following these accounts of air traffic control failings, the Chairman of the Civil Aviation Authority of Malaysia, Azharuddin Abdul Rahman, resigned on 31 July 2018.[226][227][228]

Analysis of satellite communication[edit]

The communications between Flight 370 and the satellite communication network operated by Inmarsat, which were relayed by the Inmarsat-3 F1 satellite, provide the only significant clues to the location of Flight 370 after disappearing from Malaysian military radar at 02:22 MYT. These communications have also been used to infer possible in-flight events. The investigative team was challenged with reconstructing the flight path of Flight 370 from a limited set of transmissions with no explicit information about the aircraft's location, heading, or speed.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [229]

Technical background[edit]

Aeronautical satellite communication (SATCOM) systems are used to transmit messages sent from the aircraft cockpit, as well as automated data signals from onboard equipment, using the ACARS communications protocol. SATCOM may also be used for the transmission of FANS and ATN messages, and for providing voice, fax and data links[230] using other protocols.[229][231][232] The aircraft uses a satellite data unit (SDU) to send and receive signals over the satellite communications network; this operates independently from the other onboard systems that communicate via SATCOM, mostly using the ACARS protocol. Signals from the SDU are transmitted to a communications satellite, which amplifies the signal and changes its frequency before relaying it to a ground station, where the signal is processed and, if applicable, routed to its intended destination (e.g. Malaysia Airlines' operations centre); signals are sent from the ground to the aircraft in reverse order.

When the SDU is first powered on, it attempts to connect with the Inmarsat network by transmitting a log-on request, which is acknowledged by the ground station.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [232] This is partly to determine whether the SDU belongs to an active service subscriber, and also to identify which satellite should be used for transmitting messages to the SDU.[232] After connecting, if no further contact has been received from the data terminal (the SDU) for one hour,[lower-alpha 12] the ground station transmits a "log-on interrogation" message, commonly referred to as a "ping";[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". if the terminal is active, it will respond to the ping automatically. The entire process of interrogating the terminal is referred to as a "handshake".[72][233]

Communications from 02:25 to 08:19 MYT[edit]

Although the ACARS data link on Flight 370 stopped functioning between 01:07 and 02:03 MYT (most likely around the same time the plane lost contact by secondary radar),[58]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". the SDU remained operative.[56] After last contact by primary radar west of Malaysia, the following events were recorded in the log of Inmarsat's ground station at Perth, Western Australia (all times are MYT/UTC+8):[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [58][lower-alpha 13]

- 02:25:27 – First handshake ("log-on request" initiated by aircraft)

- 02:39:52 – Ground to aircraft telephone call, acknowledged by SDU, unanswered

- 03:41:00 – Second handshake (initiated by ground station)

- 04:41:02 – Third handshake (initiated by ground station)

- 05:41:24 – Fourth handshake (initiated by ground station)

- 06:41:19 – Fifth handshake (initiated by ground station)

- 07:13:58 – Ground to aircraft telephone call, acknowledged by SDU, unanswered

- 08:10:58 – Sixth handshake (initiated by ground station)

- 08:19:29 – Seventh handshake (initiated by aircraft); widely reported as a "partial handshake'", consisting of the following two transmissions:

- 08:19:29.416 – "log-on request" message transmitted by aircraft (seventh "partial" handshake)

- 08:19:37.443 – "log-on acknowledge" message transmitted by aircraft (last transmission received from Flight 370)

The aircraft did not respond to a ping at 09:15.[58]

Inferences[edit]

A few inferences can be made from the satellite communications. The first is that the aircraft remained operational until at least 08:19 MYT—seven hours after final contact was made with air traffic control over the South China Sea. The varying burst frequency offset (BFO) values indicate the aircraft was moving at speed. The aircraft's SDU needs location and track information to keep its antenna pointed towards the satellite, so it can also be inferred that the aircraft's navigation system was operational.[234]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

Since the aircraft did not respond to a ping at 09:15, it can be concluded that at some point between 08:19 and 09:15, the aircraft lost the ability to communicate with the ground station.[72][73][233] The log-on message sent from the aircraft at 08:19:29 was "log-on request"; there are only a few reasons the SDU would transmit this request, such as a power interruption, software failure, loss of critical systems providing input to the SDU, or a loss of the link due to the aircraft's attitude.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". Investigators consider the most likely reason to be that it was sent during power-up after an electrical outage.

At 08:19, the aircraft had been airborne for 7 hours and 38 minutes; the typical Kuala Lumpur-Beijing flight is 51⁄2 hours, so fuel exhaustion was likely.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [235] In the event of fuel exhaustion and engine flame-out, which would eliminate power to the SDU, the aircraft's ram air turbine (RAT) would deploy, providing power to some instruments and flight controls, including the SDU.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". Approximately 90 seconds after the 02:25 handshake—also a log-on request—communications from the aircraft's in-flight entertainment system were recorded in the ground station log. Similar messages would be expected following the 08:19 handshake, but none were received, supporting the fuel-exhaustion scenario.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

Analysis[edit]

Two parameters associated with these transmissions that were recorded in a log at the ground station were key to the investigation:

- Burst time offset (BTO) – the time difference between when a signal is sent from the ground station and when the response is received. This measure is proportional to twice the distance from the ground station via the satellite to the aircraft and includes the time that the SDU takes between receiving and responding to the message and time between reception and processing at the ground station. This measure was analysed to determine the distance between the satellite and the aircraft at the time each of the seven handshakes occurred, and thereby defining seven circles on the Earth's surface the points on whose circumference are equidistant from the satellite at the calculated distance. Those circles were then reduced to arcs by eliminating those parts of each circle that lay outside the aircraft's range.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [234]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

- Burst frequency offset (BFO) – the difference between the expected and received frequency of transmissions. The difference is caused by Doppler shifts as the signals travelled from the aircraft to the satellite to the ground station; the frequency translations made in the satellite and at the ground station; a small, constant error (bias) in the SDU that results from drift and ageing; and compensation applied by the SDU to counter the Doppler shift on the uplink. This measure was analysed to determine the aircraft's speed and heading, but multiple combinations of speed and heading can be valid solutions.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [234]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

By combining the distance between the aircraft and satellite, speed, and heading with aircraft performance constraints (e.g. fuel consumption, possible speeds and altitudes), investigators generated candidate paths that were analysed separately by two methods. The first assumed the aircraft was flying on one of the three autopilot modes (two are further affected by whether the navigation system used magnetic north or true north as a reference), calculated the BTO and BFO values along these routes, and compared them with the values recorded from Flight 370. The second method generated paths which had the aircraft's speed and heading adjusted at the time of each handshake to minimise the difference between the calculated BFO of the path and the values recorded from Flight 370.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [59]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". A probability distribution for each method at the BTO arc of the sixth handshake of the two methods was created and then compared; 80% of the highest probability paths for both analyses combined intersect the BTO arc of the sixth handshake between 32.5°S and 38.1°S, which can be extrapolated to 33.5°S and 38.3°S along the BTO arc of the seventh handshake.[59]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

Speculated causes of disappearance[edit]

Murder/suicide by pilot[edit]

Malaysian police searched the homes of the pilots and seized financial records for all 12 crew members. The preliminary report issued by Malaysia in March 2015 stated that there was "no evidence of recent or imminent significant financial transactions carried out" by any of the pilots or crew, and that analysis of the behaviour of the pilots on CCTV showed "no significant behavioural changes".[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

However, US officials believe the most likely explanation to be that someone in the cockpit of Flight 370 re-programmed the aircraft's autopilot to travel south across the Indian Ocean.[237][238] Media reports claimed that Malaysian police had identified Captain Zaharie as the prime suspect, if human intervention were eventually proven to be the cause of Flight 370's disappearance.[239][240][241] In 2020, Tony Abbott, the Prime Minister of Australia when MH370 disappeared, disclosed in a Sky News documentary: "My very clear understanding, from the very top levels of the Malaysian government, is that from very, very early on, they thought it was murder-suicide by the pilot."[242]

The murder/suicide theory is consistent with the suggestion, by retired British aviation engineer Richard Godfrey, that the flight path of the aircraft could be plotted by analysis of the disruption to Weak Signal Propagation Reporter (WSPR) signals on the day in question. It was reported, in March 2024, that scientists at the University of Liverpool were undertaking a major new study to verify how viable the technology is, and what this could mean for locating the aircraft.[243] However the creator of WSPR, Nobel Prize laureate Joseph Hooton Taylor Jr., has stated: "I do not believe that historical data from the WSPR network can provide any information useful for aircraft tracking". Specifically relating to MH370, Taylor stated: "It's crazy to think that historical WSPR data could be used to track the course of ill-fated flight MH370. Or, for that matter, any other aircraft flight".[244]

Pilot's flight simulator[edit]

In 2016, New York magazine wrote that a confidential document from the Malaysian police investigation showed an FBI analysis of the flight simulator's computer hard drive found a route on Captain Zaharie's home flight simulator that closely matched the projected flight over the Indian Ocean and that this evidence had been withheld from the publicly released investigative report.[245] New York wrote as follows:

New York has obtained a confidential document from the Malaysian police investigation into the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 that shows that the plane's captain, Zaharie Ahmad Shah, conducted a simulated flight deep into the remote southern Indian Ocean less than a month before the plane vanished under uncannily similar circumstances. The revelation, which Malaysia withheld from a lengthy public report on the investigation, is the strongest evidence yet that Zaharie made off with the plane in a premeditated act of mass murder-suicide.

[...] The newly unveiled documents [...] suggest Malaysian officials have suppressed at least one key piece of incriminating information. This is not entirely surprising: There is a history in aircraft investigations of national safety boards refusing to believe that their pilots could have intentionally crashed an aircraft full of passengers.

The FBI's findings about the flight simulation were confirmed by the ATSB.[246] News of the simulation was also confirmed by the Malaysian government,[247] but reported as "nothing sinister".[248][249]

Power interruption[edit]

The SATCOM link functioned normally from pre-flight (beginning at 00:00 MYT) until it responded to a ground-to-air ACARS message with an acknowledge message at 01:07. At some time between 01:07 and 02:03, power was lost to the Satellite Data Unit (SDU). The final report stated "it is likely that the loss of communication prior to the diversion is due to the systems being manually turned off or power interrupted to them." Malaysian Prime Minister, Najib Razak, said it was clear that the radar transponders and the flight data transmission system were turned off deliberately by someone trying to hide the plane's position and heading.[250] At 02:25, the aircraft's SDU rebooted itself and sent a log-on request.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". [58]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

Passenger involvement[edit]

United States and Malaysian officials reviewed the backgrounds of every passenger named on the manifest.[43] One passenger, who worked as a flight engineer for a Swiss jet charter company, was briefly under suspicion as a potential hijacker because he was thought to have the relevant "aviation skills".[251]

Two men were found to have boarded Flight 370 with stolen passports, which raised suspicion in the immediate aftermath of its disappearance.[252][253] The passports, one Austrian and one Italian, had been reported stolen in Thailand within the preceding two years.[252] The two passengers were later identified as Iranian men, one aged 19 and the other 29, who had entered Malaysia on 28 February using valid Iranian passports. They were believed to be asylum seekers,[254][255] and the Secretary General of Interpol later stated that the organisation was "inclined to conclude that it was not a terrorist incident".[37]

On 18 March, the Chinese government announced that it had checked all of the Chinese citizens on the aircraft and had ruled out the possibility that any were involved in "destruction or terror attacks".[256]

Cargo[edit]

Flight 370 was carrying 10,806 kg (23,823 lb) of cargo, of which four unit load devices (standardized cargo containers) of mangosteens (a tropical fruit) (total 4,566 kg (10,066 lb)) and 221 kg (487 lb) of lithium-ion batteries were of interest, according to Malaysian investigators.[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". According to the head of Malaysian police, Khalid Abu Bakar, the people who handled the mangosteens and the Chinese importers were questioned to rule out sabotage.[257]

The lithium-ion batteries were contained in a 2,453 kg (5,408 lb) consignment being shipped from Motorola Solutions facilities in Bayan Lepas, Malaysia, to Tianjin, China. They were packaged in accordance with IATA guidelines, but did not go through any additional inspections at Kuala Lumpur International Airport before being loaded onto Flight 370;[20]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". Lithium-ion batteries can cause intense fires if they overheat and ignite, which has occurred on other flights,[258][259][260] and has led to strict regulations on transport aircraft.[261][258]

Unresponsive crew or hypoxia[edit]

An analysis by the ATSB comparing the evidence available for Flight 370 with three categories of accidents—an in-flight upset (e.g., stall), a glide event (e.g., engine failure, fuel exhaustion), and an unresponsive crew or hypoxia event—concluded that an unresponsive crew or hypoxia event "best fit the available evidence" for the five-hour period of the flight as it travelled south over the Indian Ocean without communication or significant deviations in its track,[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". likely on autopilot.[262][263] No consensus exists among investigators on the unresponsive crew or hypoxia theory.[264] If no control inputs were made following flameout and the disengagement of autopilot, the aircraft would likely have entered a spiral dive[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2". and entered the ocean within 20 nmi (37 km; 23 mi) of the flameout and disengagement of autopilot.[56]<span title="Script error: No such module "DecodeEncode".">: Script error: No such module "String2".

The analysis of the flaperon showed that the landing flaps were not extended, supporting the spiral dive at high speed theory.[265] In May 2018, the ATSB again asserted that the flight was not in control when it crashed, its spokesperson adding that "We have quite a bit of data to tell us that the aircraft, if it was being controlled at the end, it wasn't very successfully being controlled."[266]

Aftermath[edit]

Criticism of Malaysian authorities' management of information[edit]

Public communication from Malaysian officials regarding the loss of Flight 370 was initially beset with confusion.[lower-alpha 14] The Malaysian government and the airline released imprecise, incomplete, and occasionally inaccurate information, with civilian officials sometimes contradicting military leaders.[280] Malaysian officials were criticised for such persistent release of contradictory information, most notably regarding the last location and time of contact with the aircraft.[281]

Malaysia's acting Transport Minister Hishammuddin Hussein, who was also the country's Defence Minister (until May 2018), denied the existence of problems between the participating countries, but academics explained that because of regional conflicts, there were genuine trust issues involved in co-operation and sharing intelligence, and that these were hampering the search. International relations experts suggested that entrenched rivalries over sovereignty, security, intelligence, and national interests made meaningful multilateral co-operation very difficult.[282][283] A Chinese academic made the observation that the parties were searching independently, and it was therefore not a multilateral search effort. The Guardian newspaper noted the Vietnamese permission given for Chinese aircraft to overfly its airspace as a positive sign of co-operation.[283] Vietnam temporarily scaled back its search operations after the country's Deputy Transport Minister cited a lack of communication from Malaysian officials despite requests for more information.[284] China, through the official Xinhua News Agency, urged the Malaysian government to take charge and conduct the operation with greater transparency, a point echoed by the Chinese Foreign Ministry days later.[282][285]

Malaysia had initially declined to release raw data from its military radar, deeming the information "too sensitive", but later acceded.[282][283] Defence experts suggested that giving others access to radar information could be sensitive on a military level, for example: "The rate at which they can take the picture can also reveal how good the radar system is." One suggested that some countries could already have had radar data on the aircraft, but were reluctant to share any information that could potentially reveal their defence capabilities and compromise their own security.[282] Similarly, submarines patrolling the South China Sea might have information in the event of a water impact, and sharing such information could reveal their locations and listening capabilities.[286]

Criticism was also levelled at the delay of the search efforts. On 11 March 2014, three days after the aircraft disappeared, British satellite company Inmarsat (or its partner, SITA) had provided officials with data suggesting that the aircraft was nowhere near the areas in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea being searched at the time, and that it may have diverted its course through a southern or northern corridor. This information was not acknowledged publicly until it was released by the Malaysian Prime Minister in a press conference on 15 March.[229][287] Explaining why information about satellite signals had not been made available earlier, Malaysia Airlines stated that the raw satellite signals needed to be verified and analysed "so that their significance could be properly understood" before it could publicly confirm their existence.[76] Acting Transport Minister Hishammuddin claimed that Malaysian and US investigators had immediately discussed the Inmarsat data upon receipt on 12 March, and that they had agreed to send the data to the US for further processing on two separate occasions. Data analysis was completed on 14 March, by which time the AAIB had independently arrived at the same conclusion.[288]

In June 2014, relatives of passengers on Flight 370 began a crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo to raise US$100,000 (~$ in 2023)—with an ultimate goal of raising US$5 million—as a reward to encourage anyone with knowledge of the location of Flight 370, or the cause of its disappearance, to reveal what they knew.[289][290] The campaign, which ended on 8 August 2014, raised US$100,516 from 1,007 contributors.[289]

Malaysia Airlines[edit]

A month after the disappearance, Malaysia Airlines' chief executive Ahmad Jauhari Yahya acknowledged that ticket sales had declined but failed to provide specific details. This may have partially resulted from the suspension of the airline's advertising campaigns following the disappearance. Ahmad stated in an interview with The Wall Street Journal that the airline's "primary focus...is that we do take care of the families in terms of their emotional needs and also their financial needs. It is important that we provide answers for them. It is important that the world has answers, as well."[291] In further remarks, Ahmad said he was not sure when the airline could start repairing its image, but that the airline was adequately insured to cover the financial loss stemming from Flight 370's disappearance.[291][292] In China, where the majority of passengers were from, bookings on Malaysia Airlines were down 60% in March.[293]

Malaysia Airlines retired the MH370 flight number and replaced it with MH318 (Flight 318) beginning 14 March 2014. This follows a common practice among airlines to redesignate flights after notorious accidents.[294][295] As of October 2023, Malaysia Airlines still operates the Kuala Lumpur - Beijing route as MH318, however the airline now flies into Beijing Daxing rather than Beijing Capital.[296]